In this chapter, we will explore the rich history and origins of mindfulness in many cultures throughout the world. We will also discuss some of the more common terms of mindfulness in-depth, providing a solid foundation for our exploration of its clinical uses. Finally, we will discuss some of the clinical terms that, while not directly applicable to mindfulness, may be of use when considering the use of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy in clinical settings.

Cultural Origins of Mindfulness

Mindfulness has its roots in ancient contemplative traditions and philosophies. Although mindfulness is commonly seen as originating from Eastern cultures, there are elements of mindfulness in virtually every spiritual path throughout the world. Here’s a brief overview of the Eastern cultural origins of mindfulness:

Buddhist Tradition

- Theravada Buddhism: Mindfulness has its earliest and most direct roots in the Theravada Buddhist tradition. In Pali, the language of early Buddhist texts, mindfulness is often referred to as “sati.” The teachings of the Buddha emphasize the practice of mindfulness to develop insight and wisdom, leading to liberation from suffering. The Satipatthana Sutta, a foundational Buddhist text, provides detailed instructions on mindfulness meditation practices.

- Zen Buddhism: Originating in China and later spreading to Japan, Zen Buddhism emphasizes the practice of zazen or seated meditation. Mindfulness is an integral part of Zen practice, focusing on being fully present in each moment and observing one’s thoughts and sensations without judgment or assumption.

- Tibetan Buddhism: In Tibetan Buddhism, mindfulness is also a central practice, often combined with creative visualization techniques and mantra recitation. The Tibetan tradition places a strong emphasis on compassion, gratitude, and loving-kindness alongside mindfulness practice.

Hindu Tradition

In Hinduism, the practice of mindfulness can be found in various forms of meditation and yoga. The ancient texts of the Upanishads and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali describe techniques for cultivating mindfulness and concentration to attain spiritual enlightenment and inner peace.

Yoga

The practice of yoga, which originated in ancient India, includes mindfulness as a core component. Yoga combines physical postures (asanas), breath control (pranayama), and meditation to cultivate mindfulness and achieve a state of balance and harmony.

Taoist Tradition

In Taoism, a philosophical and spiritual tradition originating from China, mindfulness is integrated into practices such as Tai Chi and Qigong. These practices focus on harmonizing the body, mind, and spirit through mindful movement, breath awareness, and meditation.

Jewish and Christian Mystical Traditions

While mindfulness is most commonly associated with Eastern traditions, similar contemplative practices can also be found in Jewish and Christian mystical traditions. Practices such as contemplative prayer, meditation, and the repetition of sacred phrases or prayers (like the Christian prayer or Jewish meditation on the Torah) can foster mindfulness and spiritual connection.

Native American Traditions

Mindfulness practices can also be found within Native American traditions, although they may not always be referred to as “mindfulness” in the same way that it is understood in contemporary Western contexts. Native American cultures have rich spiritual traditions that emphasize a deep connection to the land, nature, ancestors, and the spirit world.

Here are some aspects of mindfulness and related practices in Native American traditions:

- Sacred Connection to Nature: Native American traditions often emphasize a deep respect and connection to nature. Practices such as nature walks, meditation in natural settings, and ceremonies that honor the land and its resources can foster mindfulness by encouraging individuals to be fully present and attentive to their surroundings.

- Ceremonial Practices: Ceremonies play a significant role in Native American spirituality and can be seen as forms of mindfulness practice. Ceremonies often involve rituals, prayers, chants, and dance that help participants cultivate a sense of presence, gratitude, and connection to the spiritual realm, community, and ancestors.

- Meditative Practices: Meditation and contemplative practices are also part of Native American traditions. For example, vision quests, where individuals spend time alone in nature seeking guidance from the spirit world, can be considered a form of mindfulness meditation. These practices help individuals cultivate inner awareness, clarity, and spiritual insight.

- Storytelling and Oral Traditions: Storytelling and oral traditions are essential aspects of Native American cultures. Listening to and sharing stories that convey moral lessons, wisdom, and cultural values can be a form of mindfulness by encouraging active listening, reflection, and a deeper understanding of oneself and one’s place in the world.

- Cultural Practices and Rituals: Various cultural practices and rituals, such as sweat lodge ceremonies, smudging, and drumming circles, can also foster mindfulness by creating a sacred space for introspection, healing, and connection with the community and the spirit world.

- Holistic Well-being: Native American concepts of health and well-being often emphasize a holistic approach that encompasses the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual aspects of life. Practices that promote balance, harmony, and alignment with natural cycles and rhythms can support mindfulness and overall well-being.

It is important to approach the understanding of mindfulness within Native American traditions with respect, cultural sensitivity, and a willingness to learn from the wisdom and teachings of indigenous peoples. While mindfulness practices may differ in terminology and context within Native American forms of spirituality, the underlying principles of presence, awareness, connection, and spiritual growth are universal themes that resonate with the essence of mindfulness as practiced in various traditions around the world.

Aboriginal Australian Traditions

Indigenous Australians, often referred to as Aboriginal Australians, have a deep connection to the land. Their spirituality and cultural practices involve mindfulness and a strong sense of connection to the land, to their ancestors, and to their community. Dreamtime stories and ceremonies are central to maintaining this connection and passing down traditional knowledge.

Maori Traditions

The Maori people of New Zealand have a concept known as Mauri. This term refers to the life force or essence that exists in all things. Their cultural practices, including haka (war dances) and waiata (songs), are deeply rooted in mindfulness, connecting with ancestors, and maintaining spiritual balance.

African Traditions

Various indigenous African cultures have mindfulness practices that emphasize community, ritual, and connection with the natural world. For example, in some West African cultures, drumming and dancing are used as spiritual practices to connect with ancestors and achieve a state of mindfulness.

Contemporary Nature-Centered Spirituality

In contemporary nature-centered spiritual practices, mindfulness often plays a central role as a means of deepening one’s connection to nature, the Earth, to others, to self, and the universe or a higher power. These practices draw inspiration from indigenous wisdom, ecological principles, and spiritual traditions to cultivate a sense of unity, harmony, and reverence for the natural world.

Here’s a closer look at how mindfulness is practiced in contemporary nature-centered spiritual traditions:

- Ecopsychology and Ecotherapy: These fields emphasize the healing and transformative power of nature on human well-being. Mindfulness practices are often integrated into ecotherapy sessions and ecopsychology approaches to help individuals develop a deeper connection with nature and themselves. Mindful walking, forest bathing, and nature meditation are common practices used to cultivate awareness and presence in natural settings.

- Earth-based Spirituality: Earth-based or nature-based spiritual paths, such as Wicca, Heathenism, Paganism, Druidry, and shamanism, often incorporate mindfulness as a foundational practice. Rituals, ceremonies, and seasonal celebrations in these traditions encourage participants to be fully present and aware of their surroundings, the cycles of nature, and their inner experiences. Mindfulness helps practitioners attune to the rhythms of the Earth and the energies of the natural world.

- Permaculture and Sustainable Living: Permaculture design principles emphasize mimicking natural ecosystems to create sustainable and regenerative human habitats. Mindfulness is often integrated into permaculture practices to foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of ecological processes. By practicing mindfulness, permaculture enthusiasts can observe, learn from, and engage with nature in a more conscious and harmonious way.

- Yoga and Mindful Movement: Yoga, especially styles like Hatha and Kundalini, often incorporate nature imagery and metaphors to connect practitioners with the Earth and the elements. Mindful movement, breath awareness, and meditation practices in yoga help individuals cultivate mindfulness and presence while honoring the interconnectedness of all life.

- Mindful Eco-Activism: Activists and environmentalists who practice mindfulness bring a sense of calm, compassion, and clarity to their advocacy work. Mindfulness helps them stay grounded, resilient, and effective in their efforts to protect and restore the Earth. By cultivating mindfulness, eco-activists can act from a place of awareness, empathy, and interconnectedness with nature.

- Nature Retreats and Workshops: Many retreat centers, nature reserves, and eco-villages offer mindfulness retreats, workshops, and programs that combine meditation, nature immersion, and ecological education. These retreats provide opportunities for individuals to unplug from daily stressors, reconnect with nature, and deepen their mindfulness practice in a supportive community.

In contemporary nature-centered spiritual practices, mindfulness serves as a bridge between inner and outer landscapes, helping individuals cultivate a deeper sense of connection, reverence, and responsibility towards the Earth and all its inhabitants. By practicing mindfulness in a nature-centered context, people can experience healing, transformation, and a renewed sense of purpose in their relationship with the natural world.

In all these cultures and spiritual paths, mindfulness is not just an individual practice but is deeply interconnected with community, spirituality, and the natural world. It is a way of life that fosters balance, harmony, and well-being on both personal and collective levels.

Over time, mindfulness practices from these diverse cultural and religious traditions have been adapted and integrated into secular contexts, including healthcare, psychology, education, and workplace wellness programs. This has led to the development of various mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) that are accessible to people of all backgrounds and beliefs. Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy is one of these MBIs.

It’s essential to recognize and respect the cultural origins of mindfulness while also understanding its universal applicability and adaptability to contemporary settings and contexts. As mindfulness practices continue to gain popularity in a modern context, it is essential to recognize and respect their origins in these diverse indigenous cultures. When drawing on indigenous cultural practices for inspiration for MBIs, take care to do so in a way that honors the concept’s origins and never use them in a way that is exploitative.

Mindfulness and Spirituality

As you begin to introduce the concepts of mindfulness and meditation into your therapy practice, you may notice that some of your patients may be hesitant to meditate or practice mindfulness, especially if you live in an area where a fundamentalist religion is practiced. I began my practice in the Bible Belt, and I was surprised to discover that the word “meditation” is often met with skepticism and suspicion. In certain regions of the United States and the world, meditation is sometimes associated with cults and mysticism.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, in Wherever You Go, There You Are, had this to say about meditation and religious practice:

“When we speak of meditation, it is important for you to know that this is not some weird cryptic activity, as our popular culture might have it. It does not involve becoming some kind of zombie, vegetable, self-absorbed narcissist, navel gazer, “space cadet,” cultist, devotee, mystic, or Eastern philosopher. Meditation is simply about being yourself and knowing something about who that is. It is about coming to realize that you are on a path whether you like it or not, namely, the path that is your life. Meditation may help us see that this path we call our life has direction; that it is always unfolding, moment by moment; and that what happens now, in this moment, influences what happens next.”

–from Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life

During my internship as a Marriage and Family Therapist, as I began to introduce the ideas of mindfulness and meditation into my clinical practice, I would occasionally come across a patient who felt that mindfulness was “the devil’s work.” When I addressed this issue with my clinical supervisor, he advised me to simply use the techniques without referring to them as mindfulness techniques. As I began to do this, I noticed that the preconceived notions these patients had soon evaporated. I had eliminated the resistance to the therapy by not referring to it as mindfulness. By my doing so, the client was able to see the techniques for what they were, without any preconceptions or assumptions about their content.

Although mindfulness originated with Buddhism, it is not a religious practice so much as it is a way of “falling awake.” Becoming more fully conscious of where you are and what you are doing at any given moment, you may enhance any religious practice. A careful reading of the Bible, or the Quran, or the Tao, or the Vedas, or most other works of a religious or spiritual nature, will reveal elements of mindfulness.

Spirituality in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy

Research into the benefits of spirituality has gained significant attention in recent years, with studies exploring its impact on mental health, physical well-being, and overall quality of life. While spirituality is a deeply personal and multifaceted concept, several key findings highlight its potential benefits. Here’s an overview of some recent research into the benefits of spirituality:

- Reduced Depression and Anxiety: A 2023 metastudy by Aggarwal, et al found that spirituality and religious practices can help reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety. Engaging in spiritual practices such as meditation, prayer, and attending religious services has been associated with lower levels of psychological distress.

- Increased Resilience: Manning, et al (2019) reported that spiritually oriented individuals often exhibit greater resilience in the face of adversity. Spiritual beliefs and practices can provide a sense of meaning, purpose, and hope, which can help individuals cope with life’s challenges.

- Lower Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Risk: Kobayashi, et al (2015) suggests that spirituality and religious involvement may be associated with lower blood pressure and reduced cardiovascular risk. Engaging in spiritual practices like meditation and prayer can promote relaxation and stress reduction, which may contribute to improved heart health.

- Better Immune Function: Caldeira (2023) reported that spiritual practices and beliefs can boost immune function and enhance overall immune response. A strong spiritual belief system may promote healthier lifestyle choices, such as regular exercise, balanced diet, and adequate sleep, which can support immune function.

- Greater Life Satisfaction: Spiritually inclined individuals often report higher levels of life satisfaction and overall well-being (Kreitlow, 2015). Spiritual practices can foster a sense of connection, purpose, and fulfillment, leading to a more meaningful and satisfying life.

- Improved Relationships: Spirituality can play a significant role in enhancing interpersonal relationships and social support networks (Alih, 2024). Engaging in spiritual communities, rituals, and practices often fosters a sense of belonging, empathy, and compassion toward others.

- Better Coping with Chronic Illness: Spirituality can provide comfort, solace, and strength to individuals facing chronic illness or terminal conditions (Koenig, 2012). Spiritual beliefs and practices can help individuals find meaning, acceptance, and peace in the midst of health challenges.

- Support in Grief and Loss: Spiritual beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife can offer comfort and support to individuals grieving the loss of a loved one (Biancalani, et al, 2022). Engaging in spiritual rituals, ceremonies, and practices can facilitate the grieving process and provide a sense of closure and connection.

- Improved Cognitive Abilities: Zainal & Newman (2023) suggest that engaging in spiritual practices like meditation and mindfulness can enhance cognitive function, including attention, memory, and decision-making skills. Regular spiritual practices may promote neural plasticity and cognitive resilience, contributing to better cognitive health.

- Successful Aging: Spirituality can play a crucial role in promoting successful aging by fostering resilience, adaptability, and a positive outlook on life (McManus 2024). Spiritually engaged individuals often report a higher quality of life, greater life satisfaction, and better mental health in later life.

While these findings are promising, it’s essential to recognize that spirituality is a complex and multifaceted construct that can vary greatly across individuals and cultures. Moreover, the relationship between spirituality and health is often bidirectional, meaning that spiritual beliefs and practices can influence health outcomes, and vice versa. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms underlying these relationships and to develop more personalized and integrative approaches to health and well-being that incorporate spirituality.

It is also crucial to remember that the results depend on how “spirituality” is being defined. For example, can atheists or agnostics be spiritual? Some spiritual paths (e.g., some types of Buddhism) do not require belief in any sort of deity or higher power. Some spiritual support groups, like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous, allow practitioners to view their “higher power” as their “higher self,” or what Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy and some other forms of mindfulness call the “true self.”

In this definition of spirituality, adherence to a particular religious tradition is not required to reap the benefits of a spiritual practice. All that is necessary is for the practitioner to see themselves as part of something larger than themselves.

The word “spiritual” has its roots in Latin. It comes from the Latin word “spiritualis,” which is derived from “spiritus,” meaning “breath.” In ancient times, the concept of “spiritus” was closely linked to the breath of life, the vital force that animates living beings. If you are no longer breathing, you are no longer animated, and no longer alive.

Over time, the meaning of “spiritual” evolved to encompass matters of the spirit or soul, as opposed to material or physical things. Its contemporary meaning refers to things that are concerned with religion, sacred matters, or the inner life of the individual, including beliefs, values, emotions, and intuitions.

In Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy we define “spiritual” in its original context, referring to breath. For the purposes of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, “spiritual” means “that which is breathtaking or awe-inspiring.” With this definition, even atheists or agnostics, or people with no particular spiritual or religious path, can have spiritual moments because we are all able to be inspired by transcendental experiences.

The common thread to all spiritual, or inspirational, practices is a feeling of connection. In Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy this could manifest as connection to nature, connection to others, connection to the divine or something transcendental, or simply connection to ourselves. For Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, spirituality is an inspirational sense of connectedness to something greater than ourselves.

If you think back on the spiritual experiences you’ve had in your lifetime, do recall feeling connected on some level? Many describe spiritual experiences as a sense of oneness. Oneness implies connection to something outside ourselves. In this sense, even an agnostic or an atheist could achieve spirituality through connection.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy doesn’t offer a path to a specific god or a specific divinity. What Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy does is to increase awareness and enhance the stillness so a practitioner may experience a sense of inspiration and connection in their own way. Think of the spiritual path as the road, and Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy as the vehicle. Just as you may drive a vehicle on any number of roads, you may also use Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy to experience any number of spiritual paths more fully. Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy is the tool that makes those connections possible.

Basic Concepts of Mindfulness

At its core, mindfulness is the practice of being fully present and engaged in the current moment without distraction or judgment. It involves paying attention to your thoughts, feelings, sensations, and the surrounding environment. There are many terms associated with mindfulness. In this section we’ll review some of the more common ones. There is also a glossary at the end of this book that describes and defines some of the terms used in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy and other Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs).

These terms and concepts are commonly used in clinical settings where mindfulness-based interventions are utilized to treat various mental health conditions, reduce stress, and promote overall well-being.

Family Systems Therapy

Although family systems therapy is a separate therapeutic approach from Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, the two paradigms often overlap and work well hand-in-hand. Family systems therapy is a therapeutic approach that views individuals as part of a larger system, their family. This approach to wellness emphasizes the interconnectedness of family members and the ways in which their behaviors, emotions, and interactions are influenced by the dynamics within the family unit. Family systems therapy as a rule doesn’t see problems within people, but instead views problems as difficulties in relationships and interactions within the family system. Eliminate the dysfunctional relationships, and you eliminate, or at least minimize, the problem.

Family systems therapy views the family as a complex system with its own structure, rules, and patterns of communication. It focuses on understanding how these dynamics contribute to individual behavior and emotional well-being. This form of therapy explores how each family member’s thoughts, feelings, and actions affect and are affected by other family members. It seeks to identify and address relational patterns and conflicts within the family system.

Family systems therapy takes a holistic approach to treatment, recognizing that changes in one family member can have ripple effects throughout the entire family system. It aims to promote balance, harmony, and healthy boundaries within the family.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy combines mindfulness practices with experiences in nature. It encourages individuals to cultivate present-moment awareness, non-judgmental acceptance, and connection with the natural world.

Ecotherapy draws on principles of ecopsychology, which recognizes the interconnectedness between human well-being and the natural environment. It acknowledges the therapeutic benefits of spending time in nature for mental, emotional, and physical health.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy emphasizes the embodied experience of being in nature, engaging the senses, and attuning to the rhythms and cycles of the natural world. It offers opportunities for self-reflection, relaxation, and emotional processing in a natural setting.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy aligns with the systems perspective of family systems therapy by recognizing the interconnectedness between individuals and their environment. It expands the focus of therapy beyond the family unit to include the larger ecological system in which families are embedded.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy also complements family systems therapy by providing an additional avenue for overall healing. It offers families opportunities to connect with each other and with nature, fostering a sense of unity, resilience, and well-being.

Engaging in mindfulness practices in nature can enhance family members’ awareness of their internal experiences and relational dynamics. It provides a supportive context for exploring emotions, communication patterns, and interpersonal connections within the family system.

Overall, the intersection of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy and family systems therapy offers a comprehensive approach to healing that addresses the interconnectedness of individuals, families, and the natural world. By integrating mindfulness, nature, and systemic perspectives, this approach supports families in fostering resilience, harmony, and growth.

Differentiation

One of the key concepts that family systems therapy brings to mindfulness is differentiation. Differentiation is one of the characteristics of a healthy family. Differentiation can be defined as, “the ability to separate thinking from feeling about a given relationship or situation.” When a person lacks the ability to separate their emotions from their thoughts, that person is said to be undifferentiated.

To be undifferentiated means to be flooded with feelings and powerful emotions. Such a person rarely thinks about their feelings or how to respond or react to them. They may also feel that other people should be responsible for their feelings, and that they should be responsible for the feelings of others. They lack the ability to tell where their feelings end, and other peoples’ feelings begin.

Such a relationship is called an emotionally fused relationship. Differentiation is a way to set boundaries and eliminate fusion in relationships. The process of differentiation involves learning to free yourself from emotional dependence and codependence on your family and/or romantic relationships. Differentiation involves taking responsibility for your own emotional well-being and allowing others to be responsible for their own emotional well-being. A fully differentiated person can remain emotionally attached to the family without feeling responsible for the feelings of other family members.

Mindfulness enhances differentiation by fostering self-awareness and emotional regulation, enabling individuals to clearly distinguish their own thoughts and feelings from those of others and respond thoughtfully rather than react impulsively. Through practices like meditation and mindful breathing, mindfulness helps people observe their emotions without judgment, manage stress, and maintain a balanced sense of self, which supports healthier, more autonomous interactions in relationships. This non-reactive awareness cultivates the ability to stay true to one’s values and identity while staying connected and empathetic towards others, thereby strengthening both intrapersonal and interpersonal differentiation.

Beginner’s Mind

In most forms of mindfulness-based therapy, the concept of beginner’s mind is used. Beginner’s mind is about cultivating a childlike sense of wonder about the world around us, and about ourselves. It is a way of viewing the world without assumptions, judgments, or preconceptions.

Beginner’s mind is about being childlike, but it is not about being childish. The difference between childlike and childish is that in beginner’s mind we are cultivating our mindful awareness skills to cast off our preconceived notions about the world around us to re-capture that childlike sense of wonder about life. Being childish, on the other hand, is having emotional reactions to situations that are out of our control instead of responding mindfully.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy is one way of achieving beginner’s mind. It allows us to examine the assumptions we have made about our world and how we exist in it. Some of those assumptions may be useful assumptions, but some of those assumptions may not be. By beginning each day with a blank slate, we erase those assumptions that may lead to results we don’t want.

Beginner’s mind occurs when we use the skill of being one-mindful to pay attention to our thoughts and feelings, and to the thoughts and feelings of those around us. When using mindful awareness to examine our own inner motivations, we can discover which assumptions are useful in our daily lives, and which assumptions might need to be modified, or even cast away. When being one-mindful we can practice being non-judgmental. Being non-judgmental is a critical step in achieving beginner’s mind. When we can set aside negative assumptions and perceptions and greet each day with a sense of childlike wonder, we have achieved beginner’s mind.

Being Mode

By focusing on the present moment, we leave what is referred to as thinking mode and enter into sensing mode. We leave thinking mode and enter sensing mode by shifting our attention and awareness to what our senses are experiencing. What do I see? What do I smell? What do I hear? What do I touch? What do I taste?

A common tool to shift attention to the senses is the Five Things exercise. In this activity, first name five things you see, then five things you hear, and so on until you have covered all five senses. This brings your conscious awareness out of the thinking cycle and into sensing mode. In sensing mode, we allow ourselves to become fully aware of what is going on around us and within us, without attempting to control or manipulate these events and sensations.

Sensing mode naturally leads to being mode. This is because sensing mode focuses your attention on the present moment. You cannot experience anything through your senses in the past or the future. You can only have sensations in the present moment. This present moment awareness is the essence of being mode.

Being mode reduces negative ruminations by allowing us to become aware of our thoughts and feelings as internal processes that we can choose to participate in or choose to simply observe. In being mode we learn that we are not our thoughts. We are not our feelings. Thoughts and feelings are just processes of the mind. Being mode allows us to detach from our cognitive and emotional processes and observe them, or stop them, if we choose.

Williams (2007) presents research that indicates the benefits of mindful states of being. Mindfulness is associated with decreases in levels of rumination (a process of becoming trapped in negative thought cycles), avoidance (refusing to accept the reality of a given situation), perfectionism (attempts to control a situation), and maladaptive self-guides (attempting solutions that maintain the problem). Taken together, this reduction in negative thought and behavior patterns form being mode.

Being mode reduces avoidance by allowing us to be in the present moment. If you are trying to avoid an unpleasant emotional state, you set up a cycle of denial. This denial creates anxiety and stress, which leads to more unpleasant emotional states to be avoided, which starts the avoidance cycle all over again. Being mode allows us to participate in unpleasant situations without internalizing them; without allowing the unpleasantness to become a part of our identity.

One of the common ways such ruminating cycles manifest is in the desire to be “perfect.” Perfectionism can be seen as a control mechanism. It is a displacement technique. If we feel out of control of certain areas of our lives, and we feel powerless to change those areas, we may displace our attention on the areas that we can control. By engaging in compulsive, perfectionist behaviors we assert our control over tangible areas as a substitute for areas over which we may feel we have no control. The idea of “perfection” becomes an obsessive means of anxiety management.

Being mode allows us to realize that perfection is a subjective ideal. For example, if I asked you to describe your “perfect” day, you are likely to give me a totally different answer to that question than I would give if I were asked the same question. Since our answers to the question, “What is your idea of the perfect day?” would not be identical, it can be seen that there is no objective definition to the word “perfect.” Being mode helps one to realize that perfection is a self-defined concept. In Being mode, we learn that every moment is perfect in and of itself, if we allow it to be.

Finally, being mode allows us to disengage from our own cognitive and emotional processes for a time. By doing so, we can become objective observers of our own inner states, without feeling that we must participate in them. Being mode is a type of metacognition, or “thinking about thinking.” By observing the thoughts and feelings that have led to maladaptive consequences, we gain the ability to change those thinking and feeling processes to lead to more productive conclusions.

Wise Mind

One of the skills we develop in the practice of mindfulness is the skill of acceptance. Acceptance allows us to experience emotions without feeling obligated to react to them. This is done by noting the emotion, and then letting go of the negative thought processes that the emotion generates.

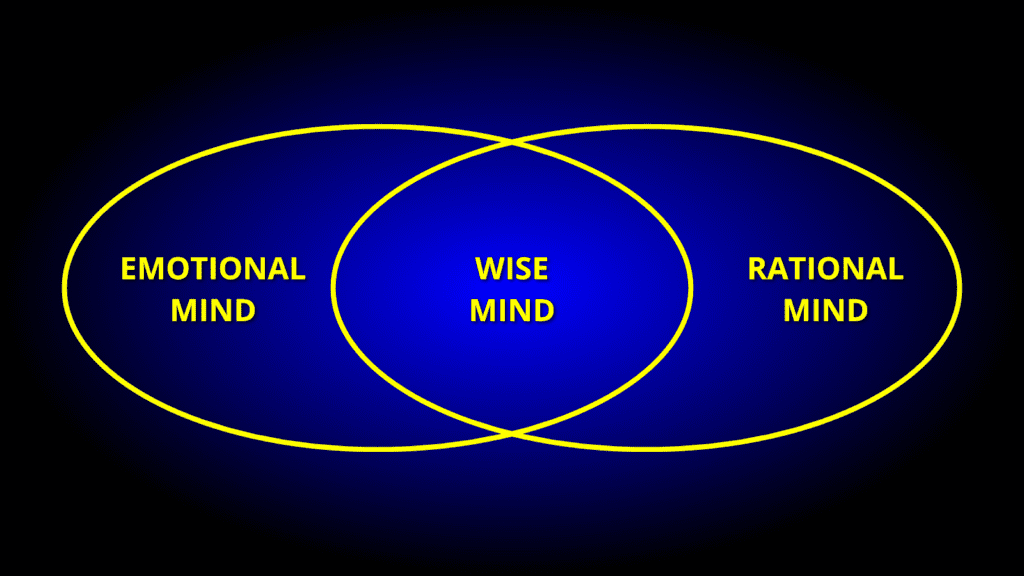

We can benefit from mindfulness by learning to accept the flood of emotions that sometimes blocks rational thought. The goal of acceptance isn’t to become a totally rational person, devoid of emotion. Instead, the goal is to practice wise mind. Wise mind is the balance of emotional mind and rational mind, in perfect harmony. From wise mind we learn that when we feel strong emotions we don’t have to do anything about them. We can just be in the moment with them.

According to Follette, et al (2006), “Wise mind is understood as a balance (or dialectic) between emotion mind and reasonable mind, where both emotion and reason are considered before taking action in life.”

This concept is often illustrated as below, where Wise Mind is the overlapping area between Rational Mind and Emotional Mind.

In the clinical practice of mindfulness, patients are often taught the concepts of Rational Mind, Emotional Mind, and Wise mind, and how to differentiate among these states. Each state has its own usefulness; for example, Rational Mind might be good for solving math problems like balancing a checkbook, while Emotional Mind might be good for a romantic interlude. But there are also situations in which one mode of mind might not be as productive as another. When using mindfulness in clinical practice, it is helpful to teach patients the concepts of Rational Mind, Emotional Mind, and Wise mind, then have them list examples of each in order to gain practice in differentiating among these states.

To illustrate this concept, let’s suppose that a destitute mother has been arrested for stealing a loaf of bread with which to feed her hungry children. If we approach this situation from Rational Mind, we are only using logic and reason. There is no emotional content to our approach to the situation in Rational Mind. In this situation, Rational Mind would say that she broke the law, and there are penalties for breaking the law, therefore she should be punished.

Wise mind, on the other hand, would allow logic and reason to be tempered with emotion. In this case, Wise mind would allow some sense of compassion for the mother and her plight. While the woman in this scenario may have broken the law, she did so because she had love for her children and did not wish to see them go hungry. Wise mind would recognize this and allow for some leniency.

What might Emotional Mind look like?

A person operating from Emotional Mind is ruled by emotions that often run out of control. The clinical term for this is emotional dysregulation. To illustrate an example of this sort of behavior, imagine that an emotionally dysregulated person has been cut off in traffic. This person becomes very angry and chases down the offender, horn blaring and lights flashing. Perhaps this person even tries to run the offender off of the road.

Such a person is ruled by Emotional Mind. If this person could learn to live in Wise mind, then he would realize that while the person who had cut him off in traffic had done something dangerous, it may not have been intentional. It could be that this person was distracted. Even if the person had done it intentionally, there is no need to increase the danger to himself by provoking further confrontation in an episode of road rage. In this case, Wise mind would accept the fact that such events are inevitable on a busy highway. The driver could introduce a little compassion into his viewpoint. Emotional Mind would then be tempered with Rational Mind, achieving the balance that is the goal of Wise mind.

Acceptance

One of the skills we develop in the practice of mindfulness is the skill of acceptance. Equanimity refers to a balanced and even-minded approach to life’s ups and downs. In clinical mindfulness, cultivating equanimity involves developing a non-reactive and accepting stance towards challenging emotions and situations. It is a way of responding to emotions instead of reacting to them from Emotional Mind. Acceptance can also mean recognizing our thoughts and feelings and accepting that we don’t have to respond or react to them in any way, but simply let them unfold in the present moment. Acceptance allows us to experience emotions without feeling obligated to react to them. This is done by noting the emotion, and then letting go of the thought processes that the emotion generates.

An undifferentiated person can benefit from mindfulness by learning to accept the flood of emotions that sometimes blocks rational thought. The goal of acceptance in differentiation isn’t to become a totally rational person, devoid of emotion. Instead, the goal is to practice wise mind. Wise mind is the balance of emotional mind and rational mind, in perfect harmony.

When we experience unpleasant emotions there is a natural tendency to want to do something to try to fix them, when in reality it is not necessary to do anything. Instead, we can just be there with the emotions, in being mode, without trying to fix them, or trying to make them go away, or trying to stop thinking about them. Trying is doing, and mindfulness is about being, not doing.

You have probably had times in your own life where you have allowed yourself to experience what you were feeling without trying to do anything about it. The goal of acceptance in differentiation isn’t to become a totally rational person, devoid of emotion. Instead, the goal is to practice Wise mind. Wise mind is the balance of emotional mind and rational mind, in perfect harmony.

A person who is able to bring acceptance into their interactions with others on a consistent basis is a person who is able to practice Wise mind. A person who is able to practice Wise mind is a differentiated person, able to separate their own emotions from the emotions of others. Acceptance is the ability to observe and describe your emotions in the present moment without feeling it is necessary to do anything about them. This naturally facilitates differentiation, ending emotional fusion in relationships.

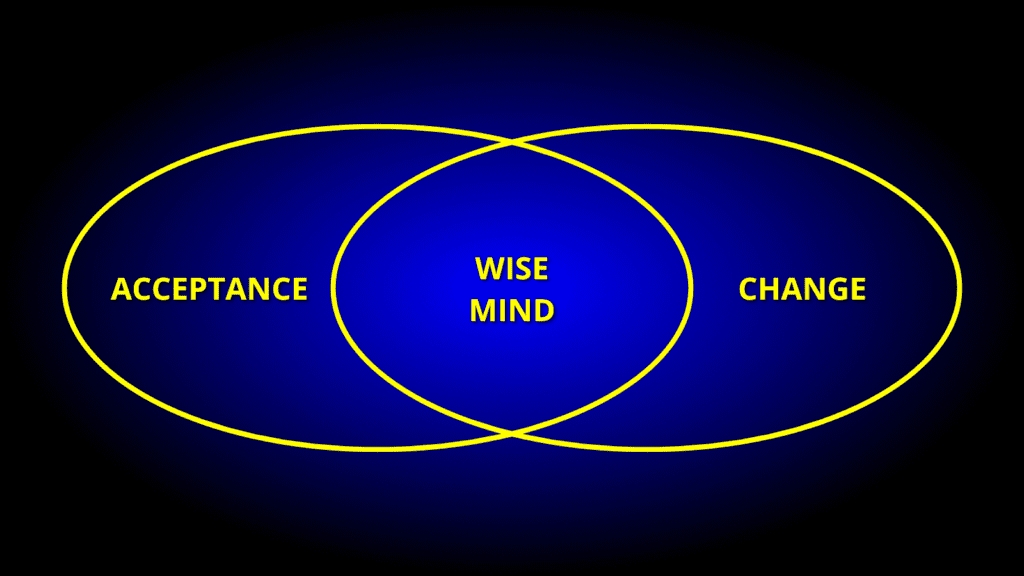

Acceptance and Change

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; courage to change the things I can; and wisdom to know the difference.”

–The Serenity Prayer of Reinhold Niebuhr

Many of us are familiar with the Serenity Prayer. It deals with the dialectic of acceptance vs. change. The key to this dialectic is the knowledge that the things we cannot change are things we must accept. Mindfulness comes from having the wisdom to know the difference. We can illustrate this concept this way:

Mindful awareness teaches us the art of acceptance. Emotional reactions to our circumstances are natural, but that doesn’t mean that we have to respond to these emotions. The mindful skill of acceptance teaches us that we can experience these emotions without engaging in cycles of behavior, thought, or feeling that lead us to negative consequences. Acceptance teaches us that we are not our thoughts, and that we are not our emotions. At any time, we can choose which thoughts and emotions we wish to respond to, and which to let go of.

From the perspective of mindful acceptance there is no such thing as a “wrong” feeling or a “bad” thought. Thoughts and feelings are just processes of the brain. What may be problematic is how we choose to respond to those thoughts or feelings. Sometimes we can choose to do nothing and simply be with the feeling. When problems arise, they most often come when we try to do something to “fix” feelings or thoughts we don’t want to experience.

Some things in life that cause us stress, anxiety and depression are things we can change. Others are things we cannot change but must learn to accept. As Niebuhr reminds us, true wisdom lies in knowing the difference between the two. In being mode, we come to recognize the fact that true happiness can only come from within. There’s good news and bad news with this realization. The bad news is that nobody can change your life circumstances but you. The good news, likewise, is that nobody can change your life circumstances but you.

Mindful acceptance includes, among other things, the idea that you can only change yourself. If your problems involve other people, then you can only accept that they are who they are. You cannot change anyone but yourself.

Mindful acceptance can best be described as the art of letting go. Once you have done everything in your power to solve a problem, you have done all you can, so at that point worry and stress is counterproductive. Letting go of the stress and anxiety doesn’t necessarily mean letting go of the problem itself. For example, suppose you have a car payment coming up, and you don’t have the money to pay it. This would naturally cause you anxiety. If, after brainstorming for solutions, you find that you still don’t have the money to pay the car payment, then at that point you’ve done all you can do.

At that point, you can let go of the anxiety associated with the problem. That doesn’t mean that you let go of car payments altogether. You’ll make the payment when you can. In this instance, “letting go” just means that you won’t worry about not being able to make the payment. The energy you might have used worrying about the situation could be put to better use in trying to come up with solutions.

Mindful acceptance is looking at the thoughts and feelings that cause you anxiety, worry, or stress. When you examine these thoughts, ask yourself which of these thoughts concern things you have the power to change. Make a conscious decision to focus your energy only on those things in your life that you have the power to change. If you focus on those things that you cannot change, you are not using your energy to change the things that you can.

Another key to mindful acceptance is to understand that anxiety has a useful purpose. It is nature’s way of letting us know that there is something wrong. Anxiety protects us from harm, but sometimes it may do its job too well.

Sometimes anxiety is trying to protect you from something that you cannot change. When this happens to you, picture yourself thanking your anxiety for protecting you, and say to your anxiety, “I am now using my own inner wisdom to make positive choices in my life.” This will work to disengage the sympathetic nervous system and engage the parasympathetic nervous system.

Mindful acceptance teaches us that each mistake is an opportunity for growth. Each mistake contains a lesson. If you never made a mistake, you would never have an opportunity to learn and grow. With mindful acceptance, you learn to accept your mistakes as signs that you are becoming a stronger and wiser individual.

Radical Acceptance

Radical acceptance is a type of mindful acceptance. Radical acceptance means learning to accept yourself and others without judgments or preconceptions. It is a skill that can be learned in an afternoon, yet take a lifetime to master, especially in Western cultures where we are conditioned to strive for certain ideals of perfection. We are told by the media that if we don’t drive the right car, wear the right clothes, eat the right food, vote for the right political candidate, and wear the right perfume, we will not be accepted by others. This conditioning must first be overcome in order to achieve radical acceptance because radical acceptance means accepting that we are perfect just as we are. As Linehan has noted, it is only when we are able to accept ourselves as we are that we can begin the process of change.

The first step in radical acceptance is to meditate on the assumptions we have created about ourselves. Examples of these might be, “I’m not handsome enough,” or, “I’m not smart enough,” or, “Nobody likes me.” Radical acceptance recognizes such thoughts and feelings without making value judgments about them, and without trying to deny or affirm them. For example, the thought, “Nobody likes me,” is not true , but the goal of radical acceptance is to simply note the fact that this thought is present in the observer’s psyche, and not to make a truth value judgment about the contents of the statement. It can be accepted as a thought process while not having to be incorporated into the observer’s sense of identity.

“Nobody likes me” is a judging statement as well, but when noting this we don’t want to get involved in saying to ourselves, “Oh no, I’ve just made a judging statement! I’m wrong for doing that!” The reason we don’t make such statements is that such statements themselves are judging statements, and we don’t want to judge our judging. If we do, we’ll continue on into endless spirals of judgment.

Instead, radical acceptance means that we always focus on trying to see the world as it is. From this perspective, we are less concerned about whether or not the thought or feeling is true as we are about whether or not it is helpful. Is it effective to have these thoughts or feelings? If not, can I let them go?

Radical acceptance is about minimizing experiential avoidance as much as possible. By meeting life head-on instead of trying to avoid certain aspects of it (such as unpleasant thoughts and emotions), we are able to live life more fully. According to Hoffman & Asmundson (2008), “Patients are encouraged to embrace unwanted thoughts and feelings – such as anxiety, pain, and guilt – as an alternative to experiential avoidance. The goal is to end the struggle with unwanted thoughts and feelings without attempting to change or eliminate them.”

Embodied Mindfulness

Embodied mindfulness is an approach to mindfulness practice that emphasizes being fully present in your body and sensations, rather than just focusing on thoughts or emotions. It involves cultivating awareness of bodily sensations, movements, and posture as a way to anchor yourself in the present moment.

Rather than just observing thoughts or feelings as they arise, embodied mindfulness encourages actively sensing and feeling into the body, noticing physical sensations such as tension, relaxation, warmth, or discomfort. By doing so, practitioners can develop a deeper connection with themselves and their surroundings, fostering a greater sense of presence and grounding.

Embodied mindfulness practices can include techniques such as body scans, mindful movement (like yoga or tai chi), or simply paying close attention to physical sensations during everyday activities like walking or eating. These practices help individuals develop a more holistic awareness that integrates mind and body, leading to greater well-being and resilience in the face of stress or challenges.

The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk (2014) explores the impact of trauma on the body and the brain. Drawing on decades of research and clinical experience, van der Kolk explains how traumatic experiences can become lodged in the body, affecting both physical and mental health.

Per van der Kolk, trauma manifests itself in the body in many ways, from PTSD to chronic pain, addiction, and dissociation. Van der Kolk explores how traditional talk therapies may not always be sufficient in addressing trauma because trauma is not only stored in memory but also in the body itself.

In this work, van der Kolk illustrates how mindful approaches such as yoga, embodied mindfulness, EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), and neurofeedback can help individuals heal from trauma by reconnecting with their bodies and reclaiming a sense of safety and control. Van der Kolk emphasizes the importance of integrating mind, body, and spirit in the healing process and highlights the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity.

Embodied mindfulness can be a powerful tool in minimizing the damage caused by adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) identified by the ACE survey. ACEs, such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, can have long-lasting impacts on physical and mental health.

Embodied mindfulness can help in many ways:

- Reconnection with the Body: ACEs often lead to a disconnection between the mind and body. Embodied mindfulness practices help individuals reconnect with their bodies, fostering awareness of physical sensations, emotions, and reactions. By paying attention to bodily sensations, individuals can learn to recognize and regulate their responses to stress and trauma, reducing the likelihood of being overwhelmed by triggering events.

- Trauma Processing: Embodied mindfulness allows individuals to explore and process trauma in a safe and supportive manner. Mindful practices like body scans or gentle movement can help individuals access and release stored trauma in the body. This can lead to a reduction in symptoms associated with PTSD and other trauma-related disorders.

- Emotional Regulation: ACEs can disrupt the development of healthy emotional regulation skills. Embodied mindfulness cultivates awareness of emotions as they arise in the body, providing an opportunity to observe and regulate them in real-time. By developing a greater capacity to tolerate and navigate difficult emotions, individuals can reduce impulsive behavior and make healthier choices in response to stressors.

- Building Resilience: Engaging in embodied mindfulness practices regularly can strengthen resilience in individuals with a history of ACEs. By fostering a sense of safety and stability in the present moment, mindfulness helps individuals develop coping strategies and adaptive responses to adversity. Over time, this can lead to increased self-efficacy and a greater sense of empowerment in managing life’s challenges.

- Improving Interpersonal Relationships: ACEs can negatively impact relationships and attachment styles. Embodied mindfulness encourages compassionate self-awareness and empathy, which can enhance communication and interpersonal connections. By developing a deeper understanding of their own needs and boundaries, individuals can cultivate healthier relationships built on trust and mutual respect.

Overall, embodied mindfulness offers a holistic approach to healing from ACEs by addressing the interconnectedness of mind, body, and spirit. By integrating mindfulness into trauma-informed care and support systems, individuals can experience profound transformations in their well-being and quality of life.

Rumination and Avoidance

Rippere (1977) defined rumination as: “enduring, repetitive, self-focused thinking which is a frequent reaction to depressed mood.” Rumination is often associated with worries about events that occurred in the past or anxiety about events that may or may not happen in the future. Rumination has been positively correlated with an increase in symptoms of depression. Learning to decrease instances of rumination has been correlated with a reduction in symptoms of depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, et al, 2009).

From a clinical standpoint, rumination could be seen as an obsession about the future. People who have a stronger tendency to ruminate also have a stronger tendency to worry about the future. They believe that their situation is hopeless; that they have no reason to expect that the future will be any different than the present or the past. By teaching them to recognize this as crystal ball thinking, they are more able to live in the moment and minimize the tendency to ruminate.

One of the keys to ending ruminating behavior may seem paradoxical at first. If a person is trapped in a cycle of rumination, such a cycle usually consists of a list of things that the person is worried about. Telling such an individual to avoid rumination is merely adding one more thing to the list of things that they already have anxiety about. Instead of focusing so much on breaking the cycle of anxiety, they should instead focus on accepting the ruminative cycle as a process of the brain. One way I’ve heard it put before is, “Your brain is going to do what your brain is going to do, but you don’t have to let it push you around.”

Rumination is also closely related to avoidance behavior. Hayes, et al (1999) conceptualize experiential avoidance behaviors as: “…unhealthy efforts to escape and avoid emotions, thoughts, memories, and other private experiences.”

Obviously, if memories are being avoided, then those memories are necessarily about events that happened in the past. Once again, if crystal ball thinking is kept to a minimum, then regrets, ruminations, and avoidance about those past events, and the thoughts and feelings associated with them, should diminish.

History and Terms of Mindfulness: Summary

This chapter provides an overview of the cultural origins, spiritual dimensions, and fundamental concepts of mindfulness, exploring its relevance to spirituality, Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy (MBE), and therapeutic practice.

The chapter examined the historical roots of mindfulness, tracing its origins to ancient contemplative traditions such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism. We highlighted mindfulness practices as integral components of spiritual and philosophical systems that emphasize present-moment awareness, introspection, and liberation from suffering. The connection between mindfulness and spirituality was explored, emphasizing mindfulness as a transformative practice that fosters spiritual growth, insight, and connection to the sacred.

The chapter examined how mindfulness intersects with various spiritual traditions, including Christianity, Judaism, Sufism, and indigenous spiritualities, reflecting diverse expressions of contemplative wisdom. The integration of spirituality into Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy (MBE) was discussed, highlighting the role of nature as a source of spiritual inspiration, healing, and transcendence. MBE is a holistic approach that honors the spiritual dimensions of human experience, fostering connection to the natural world, ecological consciousness, and reverence for life.

One of the two main core principles of MBE is mindfulness. This chapter elucidated essential concepts of mindfulness, including present-moment awareness, nonjudgmental observation, and acceptance of internal experiences. The chapter also explored mindfulness as a state of consciousness characterized by openness, curiosity, and receptivity to the unfolding of experience.

The dialectic between acceptance and change in mindfulness practice was examined, emphasizing the paradoxical nature of transformation through radical acceptance. Therapeutic approaches such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) were discussed, highlighting the integration of mindfulness with values-based action and psychological flexibility. Radical acceptance as a core principle of mindfulness was explored, emphasizing the cultivation of unconditional acceptance toward oneself, others, and life circumstances. We then looked into the liberating potential of radical acceptance in releasing resistance, reducing suffering, and fostering inner peace and equanimity.

Embodied mindfulness was introduced as an embodied approach to mindfulness practice that emphasizes somatic awareness, sensorimotor integration, and grounding in the present moment. The chapter explored the embodiment of mindfulness through practices such as mindful movement, body scanning, and sensory immersion in nature.

The detrimental effects of rumination and avoidance on mental health were examined, highlighting how mindfulness offers an antidote to habitual patterns of thought and behavior that perpetuate suffering. Strategies for addressing rumination and avoidance through mindfulness-based interventions were discussed, emphasizing present-centered awareness and compassionate self-observation.

This chapter provided an overview of the history, terminology, and foundational concepts of mindfulness, situating it within cultural, spiritual, and therapeutic contexts. By exploring mindfulness as a transformative practice that cultivates acceptance, embodiment, and spiritual awakening, the chapter highlighted its relevance to personal growth, healing, and ecological well-being in the modern world.