“I think, therefore I am.”

– Rene Descartes

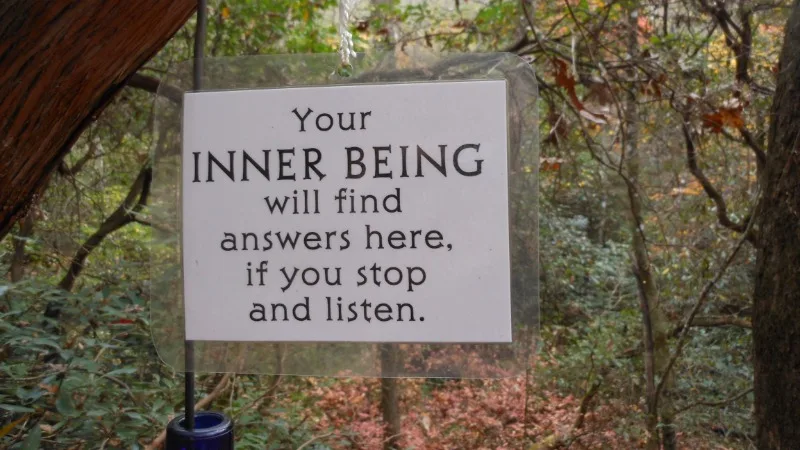

Living in the Now means increasing your mindful awareness of the present moment by leaving doing mode and entering being mode. In being mode we learn that there is no past, there is no future. There is only this present moment. Living in the Now means allowing yourself to be in the moment in which you find yourself…here and now.

The philosopher Descartes summed up Western philosophical thought in a nutshell with his statement. Western modes of thought have convinced us that we are what we think, but in reality, most of our mental suffering in life comes from the concept that we are our thoughts and feelings. In fact, I would go so far as to say that all our mental suffering is in the mind, by definition. But what if we are not our thoughts?

One way of learning to live in the now is through mindful meditation. Beginning students of mindfulness often assume that one of the goals of mindful meditation is to stop thinking. This is an oversimplification of the practice of mindful meditation, but let’s suppose for a moment that it is true. Imagine yourself sitting down to have a mindful meditation. You empty your mind and start focusing on your breathing. After a few moments pass, you have a thought. Perhaps it’s a thought like, “Why am I wasting time doing this? I have other things to do!”

As soon as you have the thought, you become aware of it, and say to yourself, “Oh no, I had a thought.” Which part of you is it that recognized that you had a thought? It can’t be your thoughts that recognized that you had a thought, because your thoughts were what you recognized in the first place. Those thoughts of “Why am I wasting time doing this? I have other things to do!” were recognized by another part of you. The part of you that recognized that you had a thought could not have been your thoughts themselves, because that’s the thing that you were recognizing: Your thoughts.

If the thing that recognizes my thoughts isn’t my thoughts, what is it? In mindfulness, we call this thought-recognizer the internal observer. In Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, we call the internal observer the True Self. This internal observation by the true self teaches us that if we are having anxious thoughts and feelings, or depressing thoughts and feelings, or stressful thoughts and feelings, those thoughts and feelings are just that: Thoughts and feelings. They are not good or bad, or true or false, unless we choose to believe that they are. We don’t have to identify with them unless we choose to do so.

When we recognize our thoughts in this manner we are engaged in metacognition. Metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” The true self is the internal mechanism that allows us to recognize that thoughts and feelings are only thoughts and feelings. They are not who we are unless we decide to let them be who we are. If I’m having anxious thoughts, I am not an anxious person. I am simply a person who is, for a time, having anxious thoughts. If I’m having depressing thoughts, I am not a depressed person. I’m just a person who is, right now, having depressing thoughts. If I am having cravings, I am not an addict. I’m just a person who is, for the moment, having addictive cravings.

This ability to separate thoughts and feelings from sense of self and self-identity is referred to as externalization. Externalization is often used to reduce anxiety and maintain self-esteem by shifting thoughts or feelings of guilt, shame, or blame away from oneself. In a therapeutic context, externalization helps individuals separate their identity from their problems, facilitating more objective problem-solving and reducing self-blame. This technique is particularly prominent in narrative therapy, where it helps clients view issues as distinct entities that can be addressed and managed.

History and Background of Living in the Now

The concept of living in the now has deep roots in various philosophical, religious, and psychological traditions worldwide. It emphasizes focusing on the present moment rather than ruminating about the past or worrying about the future. This idea has been integral to numerous cultural and intellectual movements throughout history.

The practice of mindfulness originates significantly from Buddhist teachings, particularly from the Vipassana (insight) meditation tradition. Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, taught that mindfulness (Sati) is essential for achieving enlightenment and liberation from suffering. The practice involves maintaining awareness of thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations in the present moment without judgment (Nyanaponika Thera, 1962).

The Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Hindu scripture, emphasizes living in the present and performing one’s duty without attachment to the outcomes. This concept is closely related to the idea of Karma Yoga, which involves mindful action and present-moment awareness as a path to spiritual growth (Easwaran, 2007).

In Chinese philosophy, Taoism advocates for living in harmony with the Tao, which involves embracing the flow of life and being fully present. Laozi’s Tao Te Ching teaches the importance of spontaneity, simplicity, and mindfulness in everyday life (Laozi, 1993).

Ancient Greek and Roman Stoic philosophers such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius emphasized the significance of focusing on what is within one’s control and accepting the present moment as it is. This approach involves cultivating a mindful awareness of one’s thoughts and actions (Epictetus, 2008; Marcus Aurelius, 2006).

Christian mystics and contemplatives like Brother Lawrence and St. Teresa of Avila practiced and taught the importance of present-moment awareness. Brother Lawrence’s concept of “practicing the presence of God” involves maintaining a continuous awareness of God’s presence in everyday activities (Lawrence, 1982).

In the mid-20th century, humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow emphasized the importance of being fully present and self-actualization. Rogers’ client-centered therapy focuses on the present feelings and thoughts of the client as a path to personal growth (Rogers, 1961).

Existential psychologists, such as Rollo May and Viktor Frankl, emphasized the significance of living authentically in the present moment. Frankl, in particular, highlighted the importance of finding meaning in the present, even in the face of suffering (Frankl, 1959).

In the late 20th century, Jon Kabat-Zinn pioneered the development of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), which secularized and standardized mindfulness practices for clinical use. MBSR and subsequent interventions like Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) have demonstrated the therapeutic benefits of present-moment awareness in treating stress, anxiety, and depression (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002).

The concept of living in the now has been widely popularized by authors like Eckhart Tolle, whose book “The Power of Now” (1997) became a global bestseller. Tolle’s teachings draw from various spiritual traditions and emphasize the transformative power of present-moment awareness.

Recent decades have seen a surge in scientific research on mindfulness and present-moment awareness, exploring their effects on mental and physical health. Studies have shown that mindfulness practices can improve emotional regulation, reduce stress, and enhance overall well-being (Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007).

The history and background of living in the now span ancient Eastern philosophies, Western religious traditions, modern psychological theories, and contemporary self-help movements. The enduring appeal of present-moment awareness lies in its universal application and profound impact on mental health and well-being, as demonstrated by both ancient teachings and modern scientific research.

Clinical Rationale for Living in the Now

Living in the now, often referred to as mindfulness or present-focused awareness, is a mental state achieved by focusing on the present moment while calmly acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations. This practice has been increasingly recognized for its clinical benefits across various domains of mental health.

Some of these clinical benefits include:

- Reduction in Anxiety and Depression – Mindfulness has been shown to significantly reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression. By focusing on the present moment, individuals can break the cycle of rumination and worry about the future, which are key components of anxiety and depression (Hofmann et al., 2010). This shift in focus helps individuals manage their emotional responses more effectively, thereby reducing overall distress.

- Enhanced Emotional Regulation – Practicing mindfulness enhances emotional regulation by increasing awareness of and acceptance of emotional experiences. This allows individuals to respond to stressors with greater flexibility and resilience, rather than reacting impulsively. Studies have shown that mindfulness practice leads to changes in brain regions associated with emotional regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex (Hölzel et al., 2011).

- Improved Cognitive Function – Mindfulness practice has been associated with improvements in cognitive functions, such as attention, memory, and executive function. By training the mind to stay focused on the present, individuals can enhance their ability to concentrate and process information effectively (Zeidan et al., 2010). This is particularly beneficial in reducing cognitive decline associated with aging and various mental health conditions.

- Stress Reduction – One of the primary benefits of living in the now is the reduction of stress. Mindfulness practice helps to activate the body’s relaxation response, which counteracts the stress response triggered by chronic stressors (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004). Regular mindfulness practice has been shown to reduce cortisol levels and improve stress-related biomarkers.

- Improvement in Physical Health – The practice of mindfulness not only benefits mental health but also has positive effects on physical health. Mindfulness has been linked to reductions in blood pressure, improved immune function, and better management of chronic pain (Davidson et al., 2003). By reducing stress and promoting relaxation, mindfulness can contribute to overall physical well-being.

The mindful skill of living in the now offers a wide array of clinical benefits, including reductions in anxiety, depression, and stress, enhanced emotional regulation, improved cognitive function, and better physical health. These benefits are supported by a growing body of empirical evidence, making mindfulness a valuable practice in both psychological and physical health care.

Theoretical Framework of Living in the Now

The concept of living in the now is supported by a rich theoretical framework that integrates perspectives from Eastern philosophies, Western psychology, and contemporary cognitive and behavioral sciences. This framework provides a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms and benefits of living in the present moment.

Some of the theoretical underpinnings of the concept of living in the now include:

- Central to Buddhist teachings, living in the now involves maintaining an awareness of the present moment without judgment. This practice is aimed at understanding the nature of the mind and achieving liberation from suffering (Nyanaponika Thera, 1962).

- Karma Yoga emphasizes performing one’s duties with full attention to the present moment, without attachment to the results. This practice is a path to spiritual growth and self-realization (Easwaran, 2007).

- Wu Wei refers to the principle of non-action or effortless action, which involves aligning oneself with the natural flow of life and being fully present in each moment (Laozi, 1993).

- Carl Rogers’ Client-Centered Therapy emphasizes the importance of being fully present with clients, fostering an environment of unconditional positive regard, empathy, and genuineness. This therapeutic approach aims to facilitate personal growth and self-actualization (Rogers, 1961).

- Existential psychologists like Viktor Frankl and Rollo May stress the importance of living authentically in the present moment. They highlight the need to find meaning in the present, even amidst suffering and existential challenges (Frankl, 1959; May, 1983).

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) combines mindfulness practices with cognitive-behavioral techniques to help individuals prevent depressive relapse by changing their relationship with their thoughts and feelings (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002).

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) uses mindfulness to increase psychological flexibility by encouraging individuals to accept their thoughts and feelings while committing to values-based actions (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999).

- Mindfulness practices improve the ability to sustain attention and monitor the present moment without distraction. This enhances cognitive control and reduces mind-wandering, which is associated with negative mood states (Lutz, Slagter, Dunne, & Davidson, 2008).

- Mindfulness helps individuals observe their emotions non-judgmentally, promoting healthier emotional responses and reducing reactivity (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009).

- Mindfulness fosters a compassionate attitude towards oneself, which can mitigate self-criticism and enhance emotional resilience (Neff, 2003).

- Mindfulness allows individuals to see their thoughts as transient events rather than identifying with them, reducing their impact on emotional well-being (Fresco et al., 2007).

- Regular mindfulness practice has been shown to induce structural changes in the brain, particularly in areas associated with attention, emotion regulation, and self-referential processing (Hölzel et al., 2011).

- Mindfulness enhances functional connectivity between brain regions involved in executive control and emotional regulation, leading to improved mental health outcomes (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015).

The theoretical framework of living in the now integrates ancient Eastern philosophies, Western psychological theories, and contemporary cognitive and behavioral sciences. This comprehensive approach underscores the multifaceted benefits of present-moment awareness, providing robust support for its integration into various therapeutic practices and daily life.

Mechanisms of Change for Living in the Now

The practice of living in the now is associated with several mechanisms of change that underlie its therapeutic benefits. These mechanisms operate at cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and neural levels, contributing to improvements in mental health and overall well-being. Some of these mechanisms include:

- Enhanced Attentional Control: Practicing present-moment awareness strengthens the ability to focus attention on the present moment, reducing mind-wandering and increasing cognitive control (Lutz, Slagter, Dunne, & Davidson, 2008).

- Reduced Rumination: By redirecting attention away from past regrets or future worries, mindfulness reduces rumination, which is associated with depressive symptoms and anxiety (Raes, Williams, & Hermans, 2009).

- Increased Emotional Awareness: Mindfulness enhances awareness of one’s emotional experiences without judgment or reactivity, allowing for more adaptive responses to emotions (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009).

- Emotion Regulation Strategies: Mindfulness practices promote the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as reappraisal and acceptance, which contribute to improved emotional well-being (Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2011).

- Decentering: Mindfulness fosters a decentered perspective, allowing individuals to observe thoughts and emotions as transient mental events rather than identifying with them. This reduces cognitive fusion and promotes cognitive flexibility (Fresco et al., 2007).

- Metacognitive Awareness: Mindfulness cultivates metacognitive awareness, enabling individuals to recognize and disengage from maladaptive thought patterns, such as negative self-talk or cognitive distortions (Teasdale et al., 2002).

- Values-Driven Action: Mindfulness encourages individuals to align their actions with their values and intentions, leading to more purposeful and meaningful behavior (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999).

- Reduced Impulsivity: Mindfulness practices have been associated with decreased impulsivity and improved impulse control, leading to healthier decision-making and behavior regulation (Hölzel et al., 2011).

- Brain Plasticity: Regular mindfulness practice induces structural and functional changes in the brain, particularly in regions associated with attention, emotion regulation, and self-awareness (Hölzel et al., 2011).

- Altered Resting State Connectivity: Mindfulness enhances connectivity between brain networks involved in attentional control, emotional processing, and self-referential processing, leading to improved cognitive and emotional functioning (Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015).

The mechanisms of change for living in the now encompass attention regulation, emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, and behavioral changes, all of which contribute to improvements in mental health and overall well-being. By targeting these mechanisms, mindfulness practices promote adaptive responses to stress, enhance emotional resilience, and foster a deeper sense of presence and fulfillment in everyday life.

Research on Living in the Now

Current research on the practice of living in the now, or mindfulness in the present moment, continues to shed light on its impact on mental health. Here are some recent findings:

- Mindfulness and Mental Health Outcomes – A recent meta-analysis by Goldberg et al. (2022) reviewed the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on mental health outcomes. The study found significant improvements in anxiety, depression, and stress levels among participants who engaged in MBIs compared to control groups. The findings support the growing evidence that mindfulness can be a powerful tool for improving mental health.

- Mindfulness and Neural Mechanisms – Research by Tang et al. (2023) explored the neural mechanisms underlying mindfulness meditation. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the study demonstrated that mindfulness practice increases connectivity in brain networks associated with attention, self-regulation, and emotional processing. These neural changes were correlated with reductions in symptoms of anxiety and depression, highlighting the biological underpinnings of mindfulness benefits.

- Mindfulness and Adolescent Mental Health – A study by Galla (2023) focused on the impact of mindfulness on adolescents, a group particularly vulnerable to mental health issues. The research showed that school-based mindfulness programs led to significant reductions in stress and improvements in emotional regulation among adolescents. This suggests that integrating mindfulness into educational settings can promote better mental health outcomes for young people.

- Mindfulness and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – Polusny et al. (2021) examined the effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on veterans with PTSD. The study found that veterans who participated in MBSR experienced significant reductions in PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression. These findings indicate that mindfulness can be an effective intervention for individuals suffering from trauma-related disorders.

- Mindfulness and Substance Use Disorders – Research by Garland et al. (2022) investigated the role of mindfulness in treating substance use disorders. The study found that mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (MORE) led to significant reductions in substance use and craving. Participants also reported improved emotional regulation and stress resilience, suggesting that mindfulness can be a valuable component of addiction treatment programs.

Current research underscores the significant benefits of living in the now, or mindfulness, for mental health. Mindfulness practices have been shown to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD, improve emotional regulation, and enhance neural connectivity related to attention and emotional processing. These findings highlight the importance of integrating mindfulness into therapeutic and educational settings to promote mental well-being.

Living in the Now Skills

Living in the now, or practicing mindfulness, involves cultivating certain skills that help individuals focus on the present moment. Here are some essential skills that can aid in this practice:

- Mindful Breathing involves paying close attention to the breath and noticing each inhalation and exhalation. This simple practice anchors attention to the present moment. Find a comfortable position and close your eyes. Take a few deep breaths, then allow your breath to settle into its natural rhythm. Focus on the sensation of the breath entering and leaving your nostrils or the rise and fall of your chest. When your mind wanders, gently bring your attention back to your breath.

- Body Scan – A body scan involves bringing awareness to different parts of the body, and noticing any sensations, tension, or discomfort. Lie down or sit comfortably with your eyes closed. Starting at the top of your head, slowly move your attention down through your body. Notice any sensations in each part of your body without judgment. If you find areas of tension, consciously try to relax those muscles. Scan your entire body while breathing mindfully.

- Non-Judgmental Awareness – Non-judgmental awareness means observing your thoughts, feelings, and sensations without labeling them as good or bad. Throughout your day, take moments to pause and notice your current experience. Pay attention to your thoughts and feelings without trying to change them. Practice accepting whatever arises in your awareness without judgment.

- Mindful Eating – Mindful eating involves paying full attention to the experience of eating and drinking, both inside and outside the body. Before eating, take a moment to appreciate the food. Notice the colors, textures, and aromas. Take small bites and chew slowly, savoring the taste and texture. Pay attention to the physical sensations of eating, such as the feeling of food in your mouth and swallowing. Savor every bite as if it is the last bite of food on earth, enjoying the taste by chewing slowly before swallowing.

- Grounding Techniques – Grounding techniques help bring your focus back to the present moment, especially during times of stress or anxiety. Use the 5-4-3-2-1 technique: Name five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. Plant your feet firmly on the ground and notice the sensation. Clench and release your fists, focusing on the sensation in your hands. When your attention is focused on the present moment, you are grounded.

- Mindful Walking – Mindful walking involves paying attention to the movement of your body as you walk. Walk slowly and focus on the sensation of your feet contacting the ground. Notice the movement of your legs and the shifting of your weight. Pay attention to your surroundings, the sounds, the sights, the smells, and the air on your skin. Continue walking until your attention is fully on the present moment.

- Meditation – Meditation is a formal practice that involves setting aside time to sit quietly and focus the mind. Find a quiet place to sit comfortably. Set a timer for a period that feels manageable (start with 5-10 minutes). Focus on your breath, a mantra, or a focal point. When your mind wanders, gently bring it back to your point of focus. If you note thoughts or feelings, simply note them and let them go until your awareness is fully in the present moment.

- Gratitude Practice – Practicing gratitude involves regularly reflecting on and appreciating the positive aspects of life. Keep a gratitude journal and write down three things you are grateful for each day. Reflect on these items and savor the positive feelings they bring. Practice expressing gratitude to others verbally or through written notes. Find at least one person per day to thank for something.

These skills help individuals cultivate mindfulness and live more fully in the present moment. By incorporating practices like mindful breathing, body scans, non-judgmental awareness, mindful eating, grounding techniques, mindful walking, meditation, and gratitude, practitioners can enhance their mental well-being and overall quality of life. These skills help us to become more cognizant of our thoughts and feelings in the present moment. When we understand, in the present moment, that thoughts and feelings are just processes of the mind, and not who we are, we are able to live in true self in the now of existence.

Living in the Now Interventions

Mindful present-moment awareness through living in the now has been increasingly recognized for its benefits in reducing stress, enhancing well-being, and improving overall mental health. Here are several key skills and practices associated with mindful living in the now:

- Mindful Meditation: Mindful meditation involves focusing on the present moment, often through paying attention to the breath, bodily sensations, or a particular thought. Regular practice can help cultivate a greater awareness of the present. Kabat-Zinn (2003) describes mindfulness meditation as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (p. 145).

- Deep Breathing Exercises: Deep breathing exercises are a simple yet effective way to anchor oneself in the present moment. This involves taking slow, deep breaths, and focusing on the sensation of breathing in and out. According to Brown and Gerbarg (2005), controlled breathing practices can significantly impact stress reduction and emotional regulation by engaging the parasympathetic nervous system.

- Body Scan: The body scan practice involves systematically directing attention to different parts of the body, from the toes to the head, and noticing any sensations without judgment. As described by Reiner et al. (2013), the body scan is a common mindfulness practice that enhances bodily awareness and helps in managing chronic pain and stress.

- Mindful Eating: Mindful eating entails paying full attention to the experience of eating and drinking, both inside and outside the body. It involves noticing the colors, smells, textures, flavors, temperatures, and even the sounds of our food. According to Kristeller and Wolever (2011), mindful eating can lead to a healthier relationship with food and improved eating habits by reducing binge eating and promoting a greater sense of satisfaction.

- Single-Tasking: Single-tasking is the practice of focusing on one task at a time instead of multitasking. It helps improve concentration and productivity and reduces the stress associated with juggling multiple tasks. Research by Lin and Wu (2011) suggests that single-tasking enhances cognitive performance and reduces errors, as it allows for deeper engagement and presence in the task at hand.

- Mindful Walking: Mindful walking involves paying attention to the act of walking, noticing each step, the movement of the body, and the contact with the ground. This practice can be done anywhere and helps in grounding oneself in the present. Hanson and Mendius (2009) highlight that mindful walking is a way to bring mindfulness into daily activities, promoting a sense of calm and presence.

- Gratitude Practice: Keeping a gratitude journal or regularly reflecting on things one is grateful for can shift attention away from negative thoughts and enhance overall well-being. Emmons and McCullough (2003) found that people who regularly practice gratitude report higher levels of positive emotions, life satisfaction, and physical health.

- Acceptance: Acceptance involves acknowledging and accepting thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations without trying to change or judge them. This skill is fundamental in reducing the struggle against unwanted experiences. Hayes et al. (2006) emphasize that acceptance is a core component of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which has been shown to reduce anxiety and enhance psychological flexibility.

Research continues to demonstrate the healthful benefits of practicing mindfulness through the skills of living in the now.

Living in the Now in Clinical Practice

In clinical practice, the concept of living in the now serves as a fundamental principle across various therapeutic modalities. It is integrated into treatment approaches to address a wide range of mental health concerns and promote overall well-being. In this section, we will discuss how living in the now is applied in clinical practice.

Therapists utilize mindfulness-based interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), to help clients cultivate present-moment awareness and develop mindfulness skills. In such programs clients learn to observe their thoughts and emotions in the present moment without judgment, reducing stress and anxiety. Mindfulness practices help clients disengage from rumination about the past or worry about the future, promoting mood regulation and preventing depressive relapse.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) integrates mindfulness techniques with cognitive restructuring and behavioral strategies to address maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors. Clients practice observing their thoughts in the present moment, identifying cognitive distortions, and challenging negative beliefs. By engaging in valued activities in the present moment, clients increase their sense of enjoyment and purpose, combating depression and low motivation. Mindfulness techniques, such as grounding exercises and sensory awareness, are used to help clients stay present during exposure to feared stimuli, facilitating habituation and anxiety reduction.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) combines mindfulness practices with acceptance and commitment strategies to promote psychological flexibility and values-driven action. Clients develop the ability to observe their thoughts and emotions without attachment, fostering acceptance of internal experiences and reducing experiential avoidance. Clients identify their core values and commit to actions aligned with those values, enhancing present-moment engagement and fulfillment. Clients learn to distance themselves from their thoughts, recognizing them as transient mental events rather than absolute truths, which reduces cognitive fusion and increases flexibility in responding to challenges.

Psychodynamic Therapists utilize present-moment awareness to explore clients’ unconscious processes, emotional experiences, and relational patterns. Therapists help clients stay present with their emotions in therapy sessions, facilitating deeper exploration and understanding of underlying conflicts and unresolved issues. Therapists and clients observe and reflect on their present interactions, allowing for the exploration of unconscious dynamics and relational patterns. Clients develop the capacity to observe their thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations in the present moment, enhancing self-awareness and insight into unconscious processes.

In clinical practice, living in the now serves as a foundational principle across therapeutic modalities, facilitating emotional regulation, cognitive restructuring, and behavior change. By integrating present-moment awareness into treatment approaches, therapists help clients develop mindfulness skills that promote psychological well-being, enhance resilience, and foster a deeper connection to themselves and others.

Criticisms and Limitations of Living in the Now

While the mindful skill of living in the now is a key component of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, it is not without its criticisms and limitations. Some of these include:

- Neglect of Future Planning: Critics argue that an exclusive focus on the present moment may lead individuals to neglect future-oriented thinking, such as planning for long-term goals or considering the potential consequences of actions.

- Potential for Avoidance of Difficult Emotions: Encouraging individuals to “live in the now” without addressing underlying issues may inadvertently promote avoidance of difficult emotions or unresolved problems, leading to temporary relief but hindering long-term growth.

- Lack of Contextual Understanding by Dismissal of Historical Context: The emphasis on present-moment awareness may overlook the significance of past experiences and historical context in shaping individuals’ thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

- Not Universally Applicable: Critics argue that the mindful skill of living in the now may not be suitable or effective for everyone, as individual differences and cultural factors influence the acceptance and adoption of mindfulness practices.

- Potential for Spiritual Bypassing: Some individuals may use mindfulness practices as a means of avoiding or bypassing deeper emotional or existential issues, leading to a superficial sense of well-being without addressing underlying psychological concerns.

- Commercialization and Commodification: The popularization of mindfulness in mainstream culture has led to its commercialization, with various products and services marketed as quick-fix solutions for stress reduction or self-improvement, potentially oversimplifying the practice and its benefits.

- Lack of Critical Examination: Critics argue that the mindful skill of living in the now is often presented uncritically in popular media and self-help literature, without sufficient consideration of its limitations, potential risks, or the need for individualized adaptation.

While the mindful skill of living in the now offers valuable benefits for psychological well-being and personal growth, it is important to acknowledge and address its criticisms and limitations. By promoting a balanced approach that integrates present-moment awareness with future planning, emotional processing, and contextual understanding, clinicians and practitioners can maximize the effectiveness and accessibility of mindfulness practices for diverse individuals and populations.

Living in the Now and Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy (MBE)

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy (MBE) integrates principles of mindfulness with ecotherapy practices, leveraging the natural environment to enhance mindfulness and overall well-being. This approach encourages individuals to engage deeply with nature, fostering a sense of present-moment awareness and connection to the environment. Here’s how MBE can facilitate the mindful practice of living in the now:

- Nature Immersion: Nature immersion involves spending extended periods in natural settings, such as forests, parks, or gardens. The sensory richness of these environments—sights, sounds, smells, and textures—naturally draws attention to the present moment. For example, engaging in forest bathing (shinrin-yoku), where individuals walk slowly and mindfully through a forest, paying attention to the sensory experiences around them, has been shown to reduce stress and improve mood (Hansen et al., 2017).

- Grounding Techniques: Grounding techniques in MBE use the natural environment to anchor attention in the present. This might involve walking barefoot on grass, feeling the texture of leaves, or listening to the sounds of a stream. Mindfully walking barefoot on different natural surfaces (grass, sand, soil) can enhance sensory awareness and grounding, helping individuals focus on the here and now (Jordan & Hinds, 2016).

- Nature Meditation: Nature meditation involves meditating in a natural setting, using elements of nature as focal points. This practice can enhance the depth of mindfulness by providing a dynamic and engaging environment. Meditating by a flowing river, focusing on the sound and movement of the water, can be one way to facilitate a deep sense of presence and calm (Williams & Harvey, 2001).

- Ecotherapeutic Activities: Engaging in ecotherapeutic activities like gardening, nature art (eco-art therapy), or wildlife observation can promote mindfulness by requiring full attention and engagement with the task and environment. Gardening mindfully, paying attention to the sensations of touching soil, the smells of plants, and the sights of growing flora, can be one powerful way to practice mindfulness (Clatworthy et al., 2013).

- Mindful Nature Walks: Guided mindful nature walks involve walking slowly and mindfully in nature, focusing on the sensory experience of the environment. This practice can help individuals become more attuned to their surroundings and internal experiences. A guided mindful walk in a park, with prompts to notice the colors of leaves, the sounds of birds, and the feeling of the breeze, can enhance present-moment awareness (Barton & Pretty, 2010).

- Reflective Practices: Reflective practices in MBE encourage individuals to reflect on their experiences in nature, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of the present moment. Journaling about experiences in nature, noting observations, feelings, and thoughts, can be one example of a reflective practice to help consolidate mindful experiences and enhance self-awareness (Jordan & Hinds, 2016).

- Eco-Mindfulness Exercises: Eco-mindfulness exercises are structured activities designed to cultivate mindfulness in a natural setting. These exercises often combine elements of traditional mindfulness practices with ecotherapy. An eco-mindfulness exercise might involve sitting quietly in a natural setting and focusing on the breath while also being aware of the surrounding sounds, smells, and sights, integrating both internal and external awareness (Williams & Harvey, 2001).

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy can enhance living in the now skills because nature’s calming effect can help regulate emotions and reduce stress. Regular practice of MBE can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (Berman et al., 2012). Engaging in physical activities in nature can also improve overall physical health. Fostering a deeper connection to nature can enhance environmental awareness and stewardship as well, leading to self-efficacy and gratitude for nature.

Living in the Now: Summary

Living in the now, also known as present-moment awareness, involves fully engaging with and experiencing the present moment without distraction or judgment. It is the practice of being aware of one’s thoughts, feelings, and sensations as they occur, fostering a state of mindfulness.

The concept of living in the now has roots in ancient contemplative traditions, particularly in Buddhism, where mindfulness and present-moment awareness are core practices. In the West, this concept gained prominence through the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, who developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in the late 1970s. Since then, mindfulness has become a widely researched and practiced approach in psychology and medicine.

The clinical rationale for living in the now is grounded in its effectiveness in reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. By focusing on the present moment, individuals can break free from ruminative thinking and excessive worry about the past or future. This shift in focus can lead to improved emotional regulation and mental clarity.

The theoretical framework of living in the now is based on mindfulness theory, which emphasizes nonjudgmental awareness and acceptance of the present moment. This framework is supported by cognitive-behavioral principles that highlight the role of thoughts in influencing emotions and behaviors. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) also provides a foundation, encouraging acceptance of experiences while committing to actions aligned with personal values.

Mechanisms of change for living in the now include increased awareness and acceptance of present experiences, reduced reactivity to thoughts and emotions, and enhanced self-regulation. These changes are facilitated through mindfulness practices that cultivate a greater connection to the present moment, leading to improved mental health outcomes.

Extensive research has demonstrated the benefits of living in the now. Studies have shown that mindfulness practices can reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress, improve emotional regulation, and enhance overall well-being. Neuroimaging studies suggest that mindfulness alters brain regions associated with attention, self-awareness, and emotional regulation.

Key skills for living in the now include mindfulness meditation, deep breathing exercises, body scans, mindful eating, single-tasking, mindful walking, gratitude practice, and acceptance. These skills help individuals anchor their attention in the present moment and cultivate a nonjudgmental awareness of their experiences.

Interventions designed to facilitate living in the now often involve structured mindfulness programs such as MBSR and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). These programs incorporate various mindfulness practices to help individuals develop present-moment awareness and apply it to their daily lives.

In clinical practice, living in the now is integrated into therapeutic approaches to address a range of psychological issues. Therapists may guide clients through mindfulness exercises, encourage regular practice, and help them apply mindfulness skills to cope with stress and improve mental health. MBE combines these practices with nature-based activities to enhance the therapeutic process.

Despite its benefits, living in the now is not without criticisms and limitations. Some critics argue that mindfulness practices can be challenging for individuals with severe mental health issues, such as trauma or psychosis. Additionally, the commercialization of mindfulness has led to concerns about the dilution of its core principles. There is also a need for more research on the long-term effects of mindfulness interventions.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy (MBE) integrates mindfulness practices with nature-based activities to enhance the experience of living in the now. MBE emphasizes the therapeutic potential of natural environments, encouraging individuals to engage deeply with nature to foster present-moment awareness. This approach combines the benefits of mindfulness with the restorative effects of nature, providing a holistic framework for improving mental health and well-being.

In this chapter, we explored the concept of present-moment awareness, its theoretical and clinical foundations, mechanisms of change, and practical applications. This chapter highlights the integration of mindfulness and nature through MBE, offering a comprehensive approach to enhancing mental health and fostering a deeper connection to the present moment.