Mindfulness is a mental practice characterized by the intentional focus on present-moment experiences with an attitude of openness, curiosity, and non-judgment. It involves paying attention to thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment without getting caught up in them or reacting to them.

Here is a clinical definition incorporating recent research:

“Mindfulness is a cognitive process involving the intentional, non-judgmental awareness of present moment experiences, including thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, and external stimuli. It is cultivated through mindfulness-based practices such as meditation, yoga, and mindful breathing, and is associated with enhanced emotional regulation, attentional control, and overall psychological well-being. Recent studies have shown mindfulness interventions to be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress (e.g., Goldberg et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021), improving cognitive functioning (e.g., Quach et al., 2022), and promoting resilience in the face of adversity (e.g., Galante et al., 2023).”

Mindfulness can be defined as the practice of being fully present and engaged in the current moment, with an open and non-judgmental awareness of one’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, and surroundings. It involves paying deliberate attention to experiences as they arise, without getting caught up in reacting to them or allowing them to carry one away.

Think about the last time you were stressed out or depressed about something. Hold that thought in your mind and ask yourself, “Was the stress due to something that happened in the past? Was it about something that may or may not happen in the future? How much of what I was anxious about has to do with right now, at this very moment, as I read this sentence?”

Mindfulness is a way of paying attention to what is happening right now, in this moment, with intention.

Bharate and Ray (2021) describe this as meta-awareness; or the state of being aware that you are aware. In this state of meta-cognition, we are aware of ourselves as thinking and feeling individuals. We also become aware that our thoughts and feelings are not our destiny. They are simply processes of the mind.

By focusing on our experiences in the now, from moment to moment, we come to realize that we are free to choose which thoughts and feelings to pay attention to, and which thoughts and feelings not to focus on. This doesn’t mean that we’re trying to stop thinking or feeling. It means that we’re just making a conscious choice on how much attention to focus on those thoughts or feelings. It doesn’t mean that we’re trying to avoid those thoughts or feelings either. It just means we recognize that they can’t have any influence on us unless we choose to let them.

The past only exists in our memories. The future is only a projection of the past. That is to say, the future is only our educated guesses about what we think might happen based on our past experiences. Anxiety about future events is the result of playing the odds based on past experiences and expecting similar occurrences to happen in the future. Mindfulness is a way of using the present moment to choose what to believe about the past and the future. We can choose which memories to pay attention to, and which projections about the future to focus our attention on. Mindfulness isn’t about trying to make anxious or depressing thoughts and feelings go away. It is about choosing whether or not to dwell on such thoughts and feelings.

Imagine that everything that has ever stressed you out or depressed you is written on this page. Now hold this book about six inches from your nose, or as close to your face as you can while still being able to read the words on this page. With the book this close to your face, how much of your surroundings can you see? If you’re like most people, you probably can’t see much of anything in the immediate environment except this book. You might catch a glimpse here and there of something in your peripheral vision, but overall, all you’re going to be able to see is the pages of this book.

If your stressful thoughts and feelings were written on this page, they’d be in the way of you being able to see the overall picture clearly. The words on this page would be blocking your view and making it difficult to see the big picture.

When we let our stressful thoughts and feelings occupy all our attention, then like this book, they tend to block our view of anything else that might be going on in our lives.

Instead of having all your stressful and depressing thoughts written on this page, imagine that they’re written on a boomerang. If you tried to throw that boomerang away, it would eventually come back to you. If you weren’t careful, it might actually smack you in the head on its return trip! The harder you try to throw this boomerang away, the faster it comes back to you.

When we try to “throw away” stressful and depressing thoughts and feelings, they tend to come right back at us as well. That’s because, like it or not, stressful, and depressing thoughts and feelings are just as much a part of us as happy thoughts and feelings. Trying to throw them away is trying to throw away a part of ourselves.

When we try to throw away the experience of those types of thoughts and feelings, we’re engaging in something called experiential avoidance.

Experiential avoidance refers to a maladaptive coping strategy characterized by attempts to avoid or suppress uncomfortable thoughts, emotions, memories, bodily sensations, or other internal experiences, even when doing so causes distress or interferes with valued actions and goals. This avoidance often leads to short-term relief but can perpetuate and exacerbate psychological difficulties over time.

Experiential avoidance is a cognitive-behavioral process involving efforts to avoid, suppress, or escape from aversive internal experiences such as thoughts, emotions, memories, and bodily sensations. This avoidance strategy is driven by a desire to reduce immediate discomfort but often results in long-term negative consequences, including increased psychological distress and impaired functioning.

Recent research has highlighted the role of experiential avoidance in the maintenance of various mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and chronic pain (e.g., Levin et al., 2020; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2021). Interventions targeting experiential avoidance, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness-based approaches, have shown promise in reducing symptom severity and improving overall well-being by promoting acceptance of internal experiences and encouraging valued action in the presence of discomfort (e.g., Hayes et al., 2022; Ivanova et al., 2023).”

What if, instead of trying to throw that boomerang away, you simply set it in your lap? If you did this, those negative thoughts and feelings written on the boomerang would still be with you, but they wouldn’t be blocking your view. You could still see and interact with the world, but you also wouldn’t be trying to throw away a part of yourself.

Mindfulness in this context is a way of setting that boomerang of stressful and depressing thoughts in your lap so you can see the world around you. In a 2021 study, Maher demonstrated that teaching mindfulness skills to university students helped to ameliorate symptoms of stress and performance anxiety and was an inexpensive and effective way to enhance student well-being and to improve student performance. Learning such skills helps to set the boomerang in your lap. Mindfulness is not a way of trying to throw thoughts and feelings away. Remember, if you try to do that, the boomerang may come back with a vengeance! Instead, mindfulness is about learning to accept that such thoughts and feelings are a natural part of existence and accepting that we don’t have to let them keep us from interacting with the world unless we consciously choose to do so.

Upstairs Brain vs. Downstairs Brain

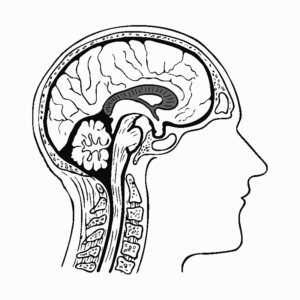

In their book, The Whole-Brain Child, Dan Siegel and Tina Payne-Bryson introduce the concepts of upstairs brain and downstairs brain as convenient metaphors for how thinking and feeling are processed in the brain.

Feelings of depression, anxiety, sadness, and other emotions are generated in a part of the brain called the limbic system. The limbic system is a complex network of brain structures primarily responsible for emotions, motivation, learning, and memory. Some parts of the limbic system include:

- Amygdala: The amygdala plays a crucial role in processing emotions, particularly fear and aggression. Recent studies have emphasized its role in social behaviors and emotional regulation (Leppänen, 2006; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005).

- Hippocampus: The hippocampus is essential for memory formation and spatial navigation. Recent research highlights its involvement in not only memory consolidation but also in the regulation of stress responses (McEwen et al., 2016).

- Hypothalamus: The hypothalamus regulates various physiological processes such as hunger, thirst, body temperature, and sexual behavior. Recent studies have explored its intricate connections with other brain regions and its involvement in homeostatic functions (Saper et al., 2005).

- Thalamus: Although traditionally not considered a part of the limbic system, the thalamus is involved in relaying sensory information to the cortex and is interconnected with limbic structures. Recent research has shed light on its role in emotional processing and integration of sensory information (LeDoux, 2007).

- Cingulate gyrus: The cingulate gyrus is involved in emotional regulation, attention, and decision-making processes. Recent studies have investigated its role in mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety (Etkin et al., 2011).

Overall, the limbic system functions through interconnected neural circuits that regulate emotions, motivation, and behavior. This “downstairs” portion of the brain also regulates the fighting, fleeing, or freezing response. In fight mode, the downstairs brain wants to protect you from harm by fighting against the threat. When it is triggered, your heart may race, your palms may get sweaty, and you may have a sharp increase in irritability and anger. In flee mode, you may experience a similar adrenaline rush, but in this instance your brain is preparing your body to run away from the danger. In freeze mode, we tend to retreat inside ourselves. This is the deer-in-the-headlights feeling of “If I’m very quiet and still, the bad thing won’t see me.”

When you’re in fight, flee, or freeze mode, your downstairs brain is preparing you to deal with a real or perceived threat in the only way it knows how. When your downstairs brain is engaged, the upstairs part of your brain tends to get overwhelmed.

The upstairs brain, in contrast, consists of the neocortex of the brain, is the part responsible for thinking things through, figuring things out, and solving problems. When the downstairs brain takes over, the upstairs brain is out to lunch. That’s why when you’re emotionally overwhelmed it is nearly impossible to figure out a way to deal with it. Your cognitive processes are being overwhelmed by your limbic system.

Upstairs brain is all about finding solutions to problems, but downstairs brain is all about fighting, fleeing, or freezing. When your upstairs brain is overwhelmed, thinking things over isn’t going to work. That’s because at that point your downstairs brain is in charge. For those times when your downstairs brain is in charge, mindfulness is a way of disengaging from the thinking cycle for a while so that you can re-center yourself and reconnect with yourself and the world around you.

If you find yourself in downstairs brain mode, where emotions are running the show, mindful states are a way to take a break for a while to allow your anxious thoughts and feelings to calm so that the upstairs brain can take charge again. Note again that mindfulness is not about “telling yourself not to think about it” or trying to avoid unpleasant feelings. Instead, it is about sitting quietly with those unpleasant feelings until you can re-engage.

In his 2020 book, Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence, Dr. Siegel demonstrates that learning emotional regulation of the downstairs brain through mindful awareness leads to improved immune system functioning, decreased inflammation, improved cholesterol, improved cardiovascular functioning, and increased neural integration.

This increased neural integration includes improved problem-solving, self-regulation skills, and improved adaptive behaviors, making it possible to adapt to new or stressful situations more easily and with less difficulty.

Doing Mode vs. Being Mode

Another aspect of mindfulness is stepping outside of doing mode and entering being mode.

The concepts of “doing mode” and “being mode” are central to mindfulness practices and represent two different ways of engaging with the present moment. Doing mode involves being goal-oriented and focused on completing tasks. In this mode, individuals are often preoccupied with planning, problem-solving, and achieving objectives. Doing mode is associated with the activation of the brain’s task-positive network, which includes regions involved in attention, cognitive control, and goal-directed behavior (Brewer et al., 2011).

Being mode, on the other hand, emphasizes present-moment awareness without judgment. In this mode, individuals cultivate an attitude of openness, curiosity, and acceptance toward their experiences. Being mode is associated with the activation of the brain’s default mode network, which includes regions involved in self-reflection, introspection, and mind-wandering (Brewer et al., 2011).

Recent studies have provided insights into the neural mechanisms underlying these two modes of engagement:

- Brewer, J. A., Garrison, K. A., & Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. (2013) asked, “what about the “self” is processed in the posterior cingulate cortex?” This study investigates the role of the posterior cingulate cortex, a key node of the default mode network, in self-referential processing and mind-wandering.

- Jha, A. P., Morrison, A. B., Parker, S. C., & Stanley, E. A. (2017) explored the cognitive benefits of mindfulness training in promoting resilience to stress, potentially through the cultivation of being mode.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015) discussed the neural mechanisms underlying mindfulness meditation practices, including their effects on attention, emotion regulation, and self-awareness.

The concepts of doing mode and being mode represent different modes of cognitive engagement with the present moment, each associated with distinct patterns of brain activity and psychological processes. Understanding these modes can inform mindfulness interventions aimed at promoting well-being and resilience.

When we’re caught up in thought and feeling cycles that lead to depression and anxiety, we usually feel that we should be doing something to fix it. The problem with this approach is that sometimes there is nothing you can do to fix a problem. Mindfulness is a way to escape this cycle of trying to fix things by simply focusing on our moment-to-moment experience. When we are doing this, we are in being mode. In being mode we are not trying to fix anything. We are not trying to go anywhere. We are not trying to do anything. We are not trying, period. Trying is doing, and being mode isn’t about doing.

In being mode we are free to enjoy our experiences from moment to moment by focusing on what our senses are telling us rather than focusing on trying to find a way out of a problem. When downstairs brain (the limbic system) is engaged, and upstairs brain (the neocortex) is temporarily disconnected, moving into being mode allows us a little breathing room.

Thinking Mode vs. Sensing Mode

The way to move from doing mode to being mode is to shift our mental energy from thinking mode to sensing mode. Thinking mode involves the continuous stream of thoughts, judgments, and evaluations that arise in the mind. In this mode, individuals are often caught up in mental rumination, planning, worrying, or analyzing past or future events. Thinking mode is associated with activity in regions of the brain’s default mode network, including the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2014).

Sensing mode emphasizes direct sensory experience and bodily sensations. In this mode, individuals shift their attention away from thoughts and into the present moment, focusing on sensory perceptions such as sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Sensing mode is associated with activation of brain regions involved in sensory processing, such as the somatosensory cortex and primary visual and auditory cortices (Farb et al., 2007).

Some recent studies have provided insights into the neural mechanisms underlying these two modes of engagement:

- Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Smallwood, J., & Spreng, R. N. (2014): This review discusses the role of the default mode network in self-generated thought, including mind-wandering and autobiographical memory retrieval, which are characteristic of thinking mode.

- Farb, N. A., Segal, Z. V., & Anderson, A. K. (2013): This study investigates the effects of mindfulness meditation training on interoceptive attention and neural representations of bodily sensations, highlighting the importance of sensing mode in mindfulness practice.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015): This review provides an overview of the neural mechanisms underlying mindfulness meditation practices, including their effects on attention, emotion regulation, and self-awareness, which are relevant to both thinking and sensing modes.

Mindfulness practices aim to cultivate awareness of both thinking mode and sensing mode and facilitate a balanced and flexible approach to experiencing reality. Our brains only have a finite of energy to spend on any given task at any given time. If we have a stressful or depressing thought cycle going on, we can shift energy from what our thoughts are telling us by engaging our internal observer to start focusing on what our senses are telling us.

As you read this paragraph, can you feel your breath going in and out of your lungs? Were you even aware you were breathing before you read the previous sentence? When caught up in thinking cycles, we’re focusing on the “boomerang” of unpleasant emotions and expecting it to return with a vengeance. By shifting our attention to our direct experiences in the present moment and focusing on what our senses are telling us, we’re able to move into sensing mode.

When in sensing mode we are no longer giving energy to ruminating cycles that are leading us to states that we do not want to experience. We can move to sensing mode by focusing first on our breathing, then on our direct sensory experiences of the current situation. We do this by using all of our senses, in the moment, to explore the environment around us. What do we hear? What do we see? What do we smell? What do we taste? What do we feel? By asking ourselves these questions, we can move into sensing mode. From sensing mode, we can more readily enter being mode.

A Tale of Two Wolves

One way to illustrate the concepts of thinking mode vs. sensing mode in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy is through the use of metaphor. A story called A Tale of Two Wolves can help in this regard.

The story is as follows:

A grandfather and his grandson were once walking through the woods, enjoying each other’s company. The grandfather noticed that the grandson was quieter than usual, so asked what was bothering him.

“I had an argument today with my best friend,” the grandson said, “and now I’m so angry with him I don’t know what to do!”

The grandfather thought about this for a moment, and answered the grandson, “I’ve had times like that myself, where I’ve been so mad I could hardly think straight. But when I feel that way, I remember that there are two wolves inside of me who are constantly at battle.”

“One wolf is the good wolf. He is calm, friendly and wise. He always looks after the pack, and always takes care of everyone, especially the ones who can’t take care of themselves.”

Grandfather continued, “The other wolf is mean, angry, and evil. He makes fun of the other wolves, and constantly starts fights. He is always angry, and he is never satisfied. These two wolves are always at war within me.”

The grandson looked at his grandfather and asked, “Which wolf will win?”

”The one I feed,” the grandfather replied.

Mindful states help us to move from thinking mode to sensing mode. The more energy we spend on sensing, the less energy we must spend on thinking. Based on the tale of two wolves above, we could see the two wolves as “thinking wolf” and “sensing wolf.”

The more energy you give to sensing wolf, the less energy you give to thinking wolf. The less energy thinking wolf receives, the weaker thinking wolf becomes. Conversely, the more energy sensing wolf receives, the stronger sensing wolf becomes. By shifting from thinking to sensing, you’re not trying to “kill” the thinking wolf. You’re not engaging in doing mode by trying to make the thinking wolf go away. You’re simply depriving it of energy so that it may eventually go away on its own. Even if it doesn’t go away on its own, you’re not focusing your attention on it. Since your attention isn’t on it, thinking wolf can’t grab you by the throat, refusing to let go.

Of course, focusing on what your senses are telling you is a type of thinking as well; however, the difference is that focusing on what your senses are telling you is a type of thinking devoid of emotional content. If you’re in a thinking cycle that is causing you anxiety or depression, then anxiety and depression are emotions. But unless you hate trees for some reason, simply sitting quietly in a forest and observing a tree as if you are an artist about to draw that tree is an exercise devoid of emotional content. By focusing on the emotionally neutral stimuli found in nature, we give ourselves the opportunity to feed the sensing wolf and deprive the thinking wolf.

The exercises in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy all involve a type of doing, but it is a type of doing that is emotionally neutral. The exercises in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, unless otherwise specified, are a type of doing that trains your brain to focus on your experiences in the here and now, devoid of troublesome emotional content.

For the purposes of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, the “thinking wolf” is analogous to the sympathetic nervous system, and the “sensing wolf” is the parasympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are two branches of the autonomic nervous system responsible for regulating involuntary bodily functions. They work together to maintain homeostasis and respond to internal and external stimuli.

The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) is often referred to as the “fight or flight” system, as it prepares the body for action in response to perceived threats or stressors. It activates physiological responses such as increased heart rate, dilation of pupils, and release of stress hormones like adrenaline and noradrenaline

Recent research by Chrousos (2021) highlights the role of the SNS in orchestrating the body’s stress response and mobilizing energy resources to cope with challenging situations. Chronic activation of the SNS has been associated with adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and metabolic disorders (Grassi et al., 2020).

The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) is often referred to as the “rest and digest” system, as it promotes relaxation, digestion, and recovery. It counteracts the effects of the SNS by slowing heart rate, constricting pupils, and promoting digestion and nutrient absorption.

Recent studies have shown that activation of the PNS is associated with improved cardiovascular function, reduced inflammation, and enhanced recovery from stress (Napadow et al., 2021). Mind-body practices such as mindfulness meditation and deep breathing have been shown to stimulate the PNS and promote relaxation and well-being (Tang et al., 2020).

The balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, known as sympathovagal balance, plays a crucial role in regulating physiological responses and maintaining health. Recent research by Thayer and Fischer (2021) emphasizes the importance of sympathovagal balance in determining individual susceptibility to stress-related disorders and cardiovascular disease.

Interventions aimed at rebalancing the autonomic nervous system, such as Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy and other mindfulness-based therapies, have shown promise in improving sympathovagal balance and mitigating the negative effects of chronic stress (Cakmak and Cevik, 2020).

Understanding the roles of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems is essential for managing stress, promoting relaxation, and maintaining overall health and well-being. Recent studies underscore the importance of modulating autonomic function through lifestyle interventions and mind-body practices to optimize physiological resilience and reduce the risk of stress-related disorders.

Engaging the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) through mindfulness practices is a powerful tool for stress reduction and overall well-being. One effective approach is through sensing mode, which involves directing attention to sensory experiences in the present moment.

Sensing mode tends to guide us naturally into being mode. The reason for this is that it is impossible to experience anything through the senses in the past or the future. We can only experience the world through our senses in the present moment. When we enter the present moment through observing with our senses, we enter being mode automatically.

There are multiple ways to engage in sensing mode. Here are a few of them:

- Body Scan Meditation: This practice involves systematically moving attention through different parts of the body, noticing sensations without judgment. A study by Bilevicius et al. (2020) found that body scan meditation was associated with increased activation of the PNS, as measured by heart rate variability (HRV), indicating a shift towards relaxation and stress reduction.

- Focused Breathing: Paying attention to the sensations of breathing can help anchor awareness in the present moment and activate the PNS. Research by Zaccaro et al. (2018) demonstrated that focused breathing techniques led to significant improvements in HRV, indicating a shift towards parasympathetic dominance.

- Sensory Awareness: Engaging with the senses, such as noticing sounds, smells, or textures, can cultivate mindfulness and stimulate the PNS. A recent study by Kerr et al. (2021) showed that sensory-focused mindfulness practices led to increased parasympathetic activity, as measured by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), indicating a relaxation response.

- Mindful Eating: Paying attention to the sensory experience of eating, such as the taste, texture, and smell of food, can promote relaxation and digestion by engaging the PNS. A study by Albers et al. (2019) found that mindful eating practices were associated with increased HRV and improved digestion, suggesting parasympathetic activation.

- Nature Immersion: Spending time in nature and engaging the senses in natural environments has been shown to promote relaxation and activate the PNS. Research by Tyrväinen et al. (2014) demonstrated that nature immersion led to increased parasympathetic activity, as indicated by HRV, suggesting a restorative effect on the nervous system.

Incorporating these mindfulness practices into daily life can help individuals cultivate a sense of relaxation and well-being by engaging the parasympathetic nervous system. By focusing attention on sensory experiences in the present moment, individuals can promote stress reduction and overall resilience.

Basics of Mindfulness

Mindfulness involves paying attention to the present moment with openness, curiosity, and acceptance. Basic mindful skills form the foundation of mindfulness practice and can be cultivated through various techniques. Some basic mindful skills include:

- Focused Attention: This involves directing attention to a specific object, sensation, or aspect of experience, such as the breath or bodily sensations. Research by Tang et al. (2020) has shown that focused attention meditation can enhance attentional control and cognitive performance by strengthening neural circuits involved in attention regulation.

- Non-judgmental Awareness: Cultivating an attitude of non-judgmental acceptance towards one’s thoughts, emotions, and sensations is a core aspect of mindfulness. A study by Park et al. (2021) found that individuals who scored higher on measures of non-judgmental awareness reported lower levels of psychological distress and greater psychological well-being.

- Observing Sensations: Mindfulness involves observing bodily sensations, thoughts, and emotions without getting caught up in them or reacting impulsively. Recent research by Kerr et al. (2021) demonstrated that sensory-focused mindfulness practices led to increased activation in brain regions associated with sensory processing and reduced activity in regions involved in self-referential processing.

- Cultivating Gratitude: Practicing gratitude involves intentionally focusing on and appreciating positive aspects of one’s life, which can enhance overall well-being and resilience. A meta-analysis by Davis et al. (2016) found that gratitude interventions were associated with significant improvements in measures of well-being, happiness, and life satisfaction.

- Compassionate Awareness: Developing compassion towards oneself and others is an integral aspect of mindfulness practice. Research by Kirby et al. (2019) demonstrated that compassion-focused interventions led to increased self-compassion and reduced self-criticism, which were associated with improvements in mental health outcomes.

By cultivating these basic mindful skills, individuals can enhance their ability to cope with stress, regulate emotions, and foster greater well-being in daily life.

Think about something that has made you anxious recently and ask yourself this: Was the anxiety a product of the circumstances in which you found yourself, or was it a result of what you believed about those circumstances? If the anxiety was a result of the circumstances themselves, then nothing can be done to change the situation, because we can’t control what goes on outside of ourselves. But if it’s the result of what we believe about those circumstances, we can consciously choose different beliefs that don’t lead to anxiety and depression.

The essence of mindfulness is accepting that while we cannot change what goes on outside of ourselves, we can change our beliefs about it so that we become proactive rather than reactive. Mindfulness accomplishes this goal through several basic skills as described by Dr. Marsha Linehan, the founder of Dialectical Behavioral Therapy. The skills of mindfulness used in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy include observing, describing, participating, being one-mindful, being non-judgmental, and being effective. Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy utilizes these six mindful skills when discussing mindful awareness. We will discuss these skills in greater depth in the next section.

The modern world has conditioned us to live in our heads. We so often get caught up in our thinking cycles that we forget how to pay attention to what’s going on right now in the world around us. This thinking process kicks into overdrive when we’re caught in depressing or anxious thought cycles. One negative thought leads to another, and another, until soon we’re caught in a speeding snowball of negativity. This negative thought cycle is often referred to as “ruminating” or “snowballing.”

We’re so conditioned to these thought cycles that sometimes we aren’t even aware that they’re happening until we suddenly find ourselves stressing out. It’s as if our thoughts are a film running at double speed. When similar ruminating thought cycles occur often enough, they can become automatic. The development of automatic thought processes is influenced by a combination of genetic predispositions, early experiences, and environmental factors. These automatic thoughts often arise spontaneously and can have a significant impact on emotions, behaviors, and cognitive patterns.

When such automatic thought patterns lead to negative consequences, the skills of mindfulness can help us to slow down, examine each component in the chain of rumination, and “reprogram” the thought processes where needed by calling them into conscious awareness.

Some of the factors influencing such automatic cycles of rumination include:

- Early Childhood Experiences: Early childhood experiences play a crucial role in shaping the development of automatic thoughts. Research by Pears and Fisher (2005) suggests that early attachment relationships and interactions with caregivers can influence the formation of cognitive schemas and automatic thinking patterns.

- Cognitive Learning: Cognitive learning processes, such as observational learning and social modeling, contribute to the development of automatic thoughts. A study by Bandura (1977) demonstrated that individuals learn cognitive scripts and automatic responses through observation and imitation of others’ behaviors.

- Cultural and Societal Influences: Cultural and societal factors also play a role in shaping automatic thought processes. Recent research by Markus and Kitayama (2021) highlights the influence of cultural values and norms on cognitive patterns and social cognition.

- Neurobiological Factors: Neurobiological factors, including genetics and brain functioning, contribute to the development of automatic thought processes. A review by Phelps (2006) discusses the role of genetic predispositions and neural circuits in the regulation of emotional responses and cognitive biases.

- Traumatic Experiences: Traumatic experiences can have a profound impact on the development of automatic thoughts, particularly negative automatic thoughts related to fear, threat, and vulnerability. Research by Teicher et al. (2016) suggests that early childhood trauma can alter brain development and increase vulnerability to negative automatic thoughts and emotional dysregulation.

- Reinforcement and Conditioning: Automatic thoughts can be reinforced through operant conditioning, where behaviors associated with specific thoughts are either rewarded or punished. Research by Skinner (1953) demonstrated the role of reinforcement in shaping behavioral responses and cognitive patterns.

Understanding the development of automatic thought processes can provide insight into cognitive-behavioral patterns and inform interventions aimed at promoting adaptive thinking and emotional regulation.

Automatic ruminating cycles are like a film projector running at double speed in our minds. What if we could somehow slow that film projector so that we could look at each thought frame by frame? By engaging our ability to observe and describe our own thoughts to ourselves, we are able to do just that. Mindfulness is a way to engage the internal observer that lives inside of each of us so that we can pay attention to life moment by moment. This ability to slow down and examine our own thought processes is metacognition.

Metacognition refers to the ability to think about one’s own thinking processes. It involves awareness and understanding of one’s own cognitive abilities, knowledge, and strategies, as well as the ability to monitor, control, and regulate one’s cognitive processes.

In essence, metacognition is thinking about thinking.

There are two main components of metacognition:

- Metacognitive Knowledge: This component involves understanding one’s own cognitive processes, such as knowing what strategies are available for problem-solving, recognizing one’s strengths and weaknesses in different cognitive tasks, and understanding the conditions under which different strategies are effective. Metacognitive knowledge also includes awareness of the nature of tasks, such as their complexity and requirements for completion.

- Metacognitive Regulation: This component involves the ability to monitor, control, and regulate our own cognitive processes. It includes strategies for planning, monitoring progress, evaluating outcomes, and making adjustments as needed. Metacognitive regulation allows individuals to adapt their cognitive strategies based on task demands and feedback, leading to more effective learning and problem-solving.

Metacognition plays a crucial role in various cognitive activities, including learning, problem-solving, decision-making, and self-regulation. By being aware of their own cognitive processes and strategies, individuals can become more efficient and effective learners and thinkers. For example, students who are aware of different learning strategies can choose the most appropriate ones for different tasks, leading to improved academic performance.

Overall, metacognition is an essential aspect of higher-order cognitive functioning, enabling individuals to monitor and control their own thinking processes, adapt to changing task demands, and ultimately enhance their learning and problem-solving abilities. Mindfulness and mindful skills are ways of achieving such metacognitive abilities.

When stressful or depressing thoughts and feelings become too much to bear, our limbic systems, or “downstairs brains” engage. When the downstairs brain is in charge, our natural tendency is to want to do something to “fix” the situation. The problem there is that the upstairs brain is the part of our minds that comes up with solutions to problems. When the downstairs brain is engaged, the only solutions we can see are those involving fighting, fleeing, or freezing. In short, when we’re stressed or depressed, the part of the brain that does the doing is temporarily out of order.

If we find ourselves in “downstairs brain” and the fight, flee or freeze response is engaged, then “doing” something to fix the problem is outside the current realm of possibility. This is why being mode is tantamount to ending these periods of emotional dysregulation. When the sympathetic nervous system has been activated by the limbic system in “downstairs brain,” we can’t use our higher cognitive functions, or “upstairs brain” to think our way out of it. Instead, we must engage the parasympathetic nervous system through being mode by sitting quietly with the thoughts and feelings until they dissipate on their own.

The paradox of sympathetic nervous system activation is that the harder we “try” to “fix” it, the more we engage the sympathetic nervous system. “Trying” is “doing,” and “doing” is engaging doing mode, and therefore engaging the sympathetic nervous system.

This means that we can’t think our way out of it. We must instead engage the parasympathetic nervous system through being mode and sensing mode. The “What” and “How” skills of mindfulness as conceptualized by Linehan in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy can help us to activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

The “What” and “How” Skills of Mindfulness

There are six skills of mindful awareness in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). They are divided up into “what” skills and “how” skills. The “what” skills are what you do to be mindful, and the “how” skills are how you do what you do to be mindful. This section lists and briefly describes each of these skills.

The “What” Skills of Mindful Awareness are observing, describing, and participating. Let’s examine these in more detail.

Observing

When we are preoccupied with thoughts of the past or the future, we are in thinking mode. Thinking mode occurs when we are stuck in the “mind trap,” re-thinking ruminating cycles that produce anxiety or depression. Thinking mode takes us away from experiencing the world directly with our senses. When we leave thinking mode and focus our awareness directly on the information provided by our senses, we enter sensing mode. Mindful awareness teaches us to focus on the world experienced directly by our senses: Touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight.

Experiencing life in sensing mode introduces us to a richer world. It is impossible to be bored or apathetic if you treat each experience as if it is happening to you for the first time. Approaching each new situation without any assumptions or expectations is referred to as beginner’s mind, or sometimes as child’s mind. Thinking mode takes us away from experiencing the world directly with our senses. In thinking mode, we are living in our heads instead of living in the moment. Mindful awareness teaches us to focus on the world experienced directly by our senses: touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight. The skill of observing involves shifting out of thinking mode and into sensing mode by observing what you are experiencing in the present moment through all of your senses.

The next time you’re outdoors, find a flower and look at it closely. It may be a flower that you’ve walked past several times before, or it may be one you’ve never seen. This time, look at it in a different way. Imagine you’re an artist who is about to draw or paint this plant. Do you see it differently when you think about it in these terms? Do you notice how many different shades of color there are in its petals and leaves? Do you see how the light and shadow fall on it? How many leaves are there? How many petals? In which direction are the petals going?

Is your experience of the flower completely new when you look at it in this way? The mindful skill of observing allows us to be present with the flower, with our environment, or with others, by focusing on our moment-to-moment experience. It is a way of leaving thinking mode and entering sensing mode. When we leave thinking mode, we become open to what our senses are telling us in the here and now.

This technique may also be used to observe our own inner cycles of thinking and feeling. If we are experiencing strong emotional states like anxiety, sadness, or depression, we may use the skill of observing, along with the skill of describing, to simply note the experience in the moment without having to react or respond to it (Brown, 2003).

This metacognition that enables observation of our own inner states is an eventual goal of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy. To gain practice with this type of metacognition, Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy starts with observing and describing things with neutral emotional content, like trees, plants, and other objects readily found in nature, before moving on to observing and describing thoughts and emotions.

Describing

This skill of mindful awareness involves observing the smallest details of an object, event or activity, then describing the experience in a non-judgmental fashion. Describing means approaching each daily activity as if you are experiencing it for the first time. Explore as many dimensions of it as you can, while describing each component to yourself.

When we gain experience with this technique, we can apply it to other areas of our lives as well. For example, by looking at your negative thought processes, and identifying and labeling them as such, you are better able to recognize them simply as processes, and not as part of who you are as a person. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) teaches you to describe experiences without judging them or labeling them as “good” or “bad.” Instead, you can label them as merely thoughts or feelings, while remembering that thoughts and feelings are not facts.

Describing works together with observing (Brown, 2007). It is a way of noting what our senses are telling us in the present moment. In the example of the tree from the previous section, describing would be used to note the characteristics of each detail of the flower. Perhaps the leaves are various shades of green. In the fall, they may be a rainbow of autumn colors. In the spring, blossoms might present a different palette. The texture of the petals might be rough or smooth, with fine variegations or with large reticulations. There will also be a specific aroma associated with each individual flower.

There may also be sounds that a particular flower makes as the wind blows through the petals. If you were a sightless person, would you be able to distinguish one flower from another simply by the sound the wind makes in the petals? Would you be able to identify a flower solely by its aroma?

These are the describing skills of mindfulness. By describing our moment-to-moment experiences to ourselves in context, we can live richer and more meaningful lives. We are also able to consciously choose to shift attention away from troubling thought and feeling patterns and onto the world of our immediate experience.

Observing and describing help us to move from doing mode to being mode. They help us to shift from thinking mode to sensing mode. While observing and describing may also be a type of thinking, and a type of doing, the difference is that these skills train us to think about our immediate experiences through our senses in the present moment.

When we’ve gained practice with observing and describing things in nature that have no heavy emotional content, then we can move on to our own inner dialogs. When it comes to regulating our emotional states, we may use our describing skills to experience strong emotions in the present. By describing these states to ourselves, we can step outside of the maelstrom of feelings that they generate. We can focus on the bigger picture without becoming overwhelmed.

This is an eventual goal of the tool of describing, but Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy starts by gaining practice with the technique by examining things with neutral emotional content. This includes anything experienced in a natural environment like rocks, trees, birds, grass, or other natural objects.

Participating

Mindful awareness allows you to experience every aspect of an activity. We have a tendency, when in thinking mode, to see things and activities as either “all bad” or “all good.” This is not necessarily an accurate depiction of reality. Most activities aren’t inherently good or bad. We’ve taught ourselves to think of them in such terms, but we can also teach ourselves to think in a different way.

Think about an unpleasant activity that you have to engage in on a regular basis, such as washing the dishes or taking out the trash. Can you think of any pleasant aspects of these activities? There are enjoyable aspects to every experience if we train ourselves to look for them. Life occurs in the present moment. Mastering the art of participation allows us to get the most out of life in the present.

The mindful skill of participating involves fully engaging in the present moment and actively participating in one’s experiences without judgment or attachment. It entails being fully present and involved in whatever activity one is engaged in, whether it’s a routine task, social interaction, or leisure activity.

Participating mindfully requires being fully present in the here and now, rather than being preoccupied with past regrets or future worries. By directing attention to the present moment, individuals can fully immerse themselves in their experiences and appreciate the richness of each moment as it unfolds.

Mindful participation involves adopting a non-judgmental attitude towards one’s experiences, thoughts, and emotions. Rather than evaluating experiences as good or bad, right or wrong, individuals observe their experiences with curiosity, openness, and acceptance. This attitude allows for a deeper and more authentic engagement with life’s experiences.

Participating mindfully requires actively engaging in one’s experiences with intention and purpose. It involves putting aside distractions and giving one’s full attention to the task at hand, whether it’s cooking a meal, having a conversation, or engaging in a hobby. By immersing oneself fully in the present moment, individuals can derive greater satisfaction and meaning from their activities.

Mindful participation also involves letting go of attachments to outcomes or expectations. Instead of being focused on achieving a particular result or outcome, individuals approach their experiences with a sense of openness and curiosity, allowing them to fully appreciate the process rather than being fixated on the end result.

Participating in activities mindfully can foster a deeper sense of connection with oneself, others, and the world around them. By bringing awareness and intentionality to their interactions and experiences, individuals can cultivate richer and more meaningful relationships, as well as a greater sense of connection to the world.

The mindful skill of participating involves being fully present, non-judgmentally engaged, and actively involved in one’s experiences. By cultivating this skill, individuals can enhance their ability to derive satisfaction, meaning, and fulfillment from the present moment, leading to greater overall well-being and a deeper sense of connection to life.

That concludes our discussion on the “What” skills of mindfulness. Now let’s review the “How” skills. The “How” Skills of Mindful Awareness are being non-judgmental, being one-mindful, and being effective.

Being Non-judgmental

Mindful awareness teaches us the art of acceptance. Emotional reactions to our circumstances are natural, but that doesn’t mean that we have to respond to these emotions. There’s no such thing as a “wrong” feeling. What may be “wrong,” or less effective, is how we choose to respond to the feeling.

The mindful skill of being non-judgmental teaches us that we can experience emotions without engaging in cycles of behavior that lead us to negative consequences. We can choose which thoughts and emotions we wish to respond to, and which just to sit quietly with, in being mode.

Being non-judgmental means seeing the world as it is, without judgments or assumptions. When we can do so, we have achieved beginner’s mind or child’s mind, which is the art of experiencing everything as if seeing it for the first time, without placing any judgments or assumptions on the situation.

Think about how many times in the past stressful and depressing thoughts may have arisen because you misjudged a person, place or situation. Such misjudging usually happens by making assumptions about the person’s intentions or about the situation. The mindful skill of being non-judgmental is the skill of letting go of our preconceptions and assumptions about others. It means letting go of judgments about the way the world works, especially if those judgments lead to negative consequences. It also means letting go of our own negative self-judgments.

Consider this example of how judgments can alter our reality:

Suppose I have a bad experience that leads me to make the judgment that “everyone is out to get me.” That judgment is going to set my perception filter to look for evidence that confirms this assumption, while rejecting evidence that denies this assumption. This means that I’m going to see only the things that I want to see. In this case, the things I’ve set my perception filter to see are the things that affirm my judgment that “everybody is out to get me.”

Notice that once I’ve set my perception filter in this way, everyone starts looking like they’re out to get me. Suppose I meet someone who is being nice to me. This person is treating me well, because this person is friendly and interested in a relationship and is not “out to get me.” But since my perception filter is set based on the assumption, “everyone is out to get me,” I’m going to perceive this person’s niceness as an attempt to butter me up so that they may take advantage of me later. My perception filter sees a person who is being nice because they want something from me.

Now further suppose that I go around treating everyone I meet as if they’re out to get me, based on this judgment and this assumption. What’s going to happen? Isn’t it likely that all the nice people in my life will eventually get tired of being treated like they’re up to something? When they finally get tired of being treated in this way, they’re going to stop trying to interact with me. That means that the people who really aren’t out to get me will eventually go away, and soon the only people who will interact with me are the people who really are out to get me. By making a judgment, I’ve created a reality in which everyone I meet is out to get me.

Being non-judgmental teaches us not to have false expectations about ourselves and others. Being non-judgmental means not making assumptions that can cause our perception filters to create realities we may not want to experience. When we have learned the art of being non-judgmental, we have learned to be with others and with ourselves in the moment, free of judgments, assumptions and false perceptions about ourselves, others, nature, and the world around us.

Being One-mindful

Being “one mindful” simply means focusing on one thing at a time. Being one-mindful allows us to live in the present moment. Emotional dysregulation often occurs because we tend to focus on all the emotionally overwhelming aspects of a situation while thinking we have to do something to fix it. Wanting to fix it is “doing mind.” Being one-mindful allows us to shift to “being mind” and just be with the emotion without having to do anything about it.

The most effective way to do this is to first ask yourself, “What is the smallest thing I can do in this situation that will make a difference? Do that, and then if you have any energy left over you can focus on the next step, and so on, until the journey is completed. When you learn to do this, you will have learned to be one-mindful.

The mindful skill of focusing on one thing at a time, or what Linehan calls “one-mindfulness,” (Dimeff & Linehan, 2001) works together with fully participating. Focusing on one thing at a time means not getting caught up in endless to-do lists until we overwhelm ourselves. The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step. If we focus on the thousand miles, we’ll be too overwhelmed to take the first step; but if we focus only on the first step, then the next, then the next, eventually the journey will be over and we will have reached our destination.

By focusing only on one step, or on one thing, at a time, mindfulness allows us to let go of the anxiety that comes with having a full agenda.

A way to practice focusing on one thing at a time in our daily lives is to ask ourselves, “What is the smallest step I can take today that will make a difference?” while remembering that sometimes the answer to that question might be, “No steps at all.” Mindful awareness allows us the wisdom to know that sometimes it’s okay if the only things we do today are to breathe and to enjoy life in the moment.

One way to accomplish this goal is to ask ourselves, “What is the worst thing that could happen in this situation?”

This doesn’t mean that we’re being dismissive of the situation. Instead, it means that we are consciously evaluating things to see what might happen if we lose sight of our goals. If we can identify what the worst thing is in each situation, and we can prepare ourselves for it, then anything else that may happen is already accounted for.

For example, if I’m stressed out about a huge project at work, I am probably worried that I might not get the project completed by the deadline. If I don’t make the deadline, the worst thing that can happen in that situation is that I may get fired if I don’t complete the project on time. I could prepare myself for the worst thing by asking myself, “Is it really likely that they’d fire me for not completing this project on time? Can my company really afford to lose an employee who stresses out this much about missing a deadline?”

If I judge the answer to this question to be “yes,” then I might want to ask myself if I really want to work for a company that places so little value on employees who try their best.

And of course, if the answer is “no,” then I may be needlessly stressing myself out over an outcome even I don’t think is likely to occur. In such a case, the ability to focus on one thing at a time might be the thing that allows me to set aside my anxiety and concentrate on the job at hand so that I can complete it one step at a time, and to make the deadline (Linehan, 1993).

Being Effective

This is probably the most important skill of mindful awareness because it teaches us to focus on solutions, not problems. We can talk about problems all day, but until we start talking about solutions, nothing will ever get solved. The way to solve a problem is to take positive, intentional steps towards finding a solution. A mindful life is a life lived deliberately and effectively. It is a purposeful life. Being effective means solving problems in a purposeful, intentional manner. The way to be effective is to begin by asking two questions:

- What is my intention in this situation?

- Are my thoughts, feelings, and behaviors going to help me to achieve this intention?

We can talk about problems all day, but until we start talking about solutions, nothing will ever get solved. The way to solve a problem is to take positive, intentional steps towards finding a solution.

All the skills of mindfulness come together in the power of intention (Mehlum, 2020). The key to being effective in life is to do things intentionally. A mindful life is a life lived deliberately. Such a consciously lived life is not driven about on the winds of whim and fate. It is a purposeful life. The power of intention helps us to solve problems in an effective manner. It is possible to live a life of purpose through tapping into this power. When we live in mindful awareness, our thoughts, behaviors, and actions always support our intentions. When we learn to do this, we have learned how to be effective.

As previously noted, the “what” skills teach us what to do to be mindful, and the “how” skills teach us how to be mindful. Note that the “how” skills all start with the word “being.” This is a gentle reminder that mindfulness occurs in being mode. When we practice the “how” skills of mindfulness, we are coming from being mode in a mindful manner.

Benefits of Mindfulness

Practicing mindfulness has been associated with a wide range of benefits for mental, emotional, and physical well-being. Some of these benefits include:

- Stress Reduction: Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to reduce stress and improve stress coping abilities. A meta-analysis by Creswell et al. (2014) found that mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs led to significant reductions in stress levels across various populations, including clinical and non-clinical samples.

- Improved Emotional Regulation: Mindfulness practice has been linked to enhanced emotional regulation skills, including the ability to recognize, understand, and manage one’s emotions. Research by Arch and Craske (2006) demonstrated that mindfulness training led to improvements in emotion regulation and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- Enhanced Cognitive Functioning: Mindfulness meditation has been associated with improvements in cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and executive functioning. A study by Tang et al. (2007) found that participants who underwent mindfulness training showed significant improvements in attentional control and cognitive flexibility compared to a control group.

- Reduced Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression: Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. A meta-analysis by Hofmann et al. (2010) demonstrated that mindfulness-based therapy was associated with large effect sizes for reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression across various populations.

- Better Sleep Quality: Mindfulness practices have been found to improve sleep quality and reduce insomnia symptoms. Research by Black et al. (2015) showed that mindfulness-based interventions led to significant improvements in sleep quality and reductions in insomnia severity compared to control groups.

- Enhanced Well-being and Quality of Life: Mindfulness practice has been linked to greater subjective well-being and overall quality of life. A meta-analysis by Khoury et al. (2015) found that mindfulness-based interventions were associated with medium to large effect sizes for improving measures of well-being and quality of life.

- Bharate (2021) reported that practicing mindfulness leads to meta-awareness. In simple terms, meta-awareness is being aware that you are aware. It is the ability to be consciously able to examine your thought stream, with intention. When you can achieve this state, Bharate notes that experienced mindful practitioners can, through the power of meta-awareness, replace distressing thoughts like aggression, jealousy, lust, despondency, and other negative emotions by cultivating their opposites in the form of virtuous thoughts.

- Behan (2020) studied the benefits of mindful practices during the pandemic of 2020 and found that the practice of mindful meditation eased the stress and anxiety that the crisis caused.

- Brown (1984) demonstrated that those who regularly practice mindful meditation improve their visual sensitivity, increasing their ability to observe and perceive things in the environment.

- Carlson, et al (2004) found that practicing Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) improved quality of life, mood, and stress levels and decreased cortisol levels in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Cortisol is a hormone that is produced during stress. A decrease in the cortisol level means the body is under less stress.

- Fuller (2021) studied children and their responses to the 2020 pandemic. She found that introducing mindfulness skills to children improved their ability to cope with stress and depression and ameliorated some of the stress and depression related to the pandemic.

- Maher (2021) found that teaching university students mindful skills decreased their stress. The more mindful skills the students practiced, the less stress they encountered, leading to increased school performance, better attention and concentration, and the ability to stay on-task. Her conclusion was that teaching mindful skills to university students was an effective, low-cost way to promote and establish mental health in the university system.

These findings highlight the diverse range of benefits associated with mindfulness practice, spanning mental, emotional, and physical domains. By cultivating present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance, mindfulness can promote resilience, enhance coping abilities, and contribute to overall well-being. Throughout the rest of this text, we will be referring to more of these studies. For more information or further study see the References section at the end of this book.

Introduction to Mindfulness: Summary

In this introductory chapter, we provided an overview of the concept of mindfulness, its origins, principles, and practical applications. It serves as a foundational introduction for readers who are new to mindfulness or seeking to deepen their understanding of this transformative practice.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy consists of two primary skill sets: Mindfulness and ecotherapy. In this chapter we introduced the concept of mindfulness and reviewed some of its skills and benefits, including what the current research indicates on the subject.

Mindfulness is a cognitive process involving the intentional, non-judgmental awareness of present moment experiences, including thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, and external stimuli. It is cultivated through mindfulness-based practices such as meditation, yoga, and mindful breathing, and is associated with enhanced emotional regulation, attentional control, and overall psychological well-being. Mindfulness involves cultivating an attitude of curiosity towards one’s experiences, as well as a compassionate stance towards oneself and others.

In Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy we often utilize mindfulness as a tool to aid in emotional regulation. An aspect of emotional regulation involves the conceptual tool of “Upstairs Brain vs. Downstairs Brain.” The “downstairs brain” of the limbic system regulates the fight, flight, or freeze response inherent in most emotional dysregulation. When the fight, flight, or freeze response of downstairs brain is activated, the Sympathetic Nervious System (SNS) is engaged. When the SNS is activated, it can only be disengaged through the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS).

One way to engage the PNS is by leaving doing mode and entering being mode. Being mode activates the PNS because in being mode we are not trying to go anywhere, do anything, or solve any problem. In being mode we are able to just sit quietly with our thoughts and feelings until they dissipate on their own. Even if those thoughts and feelings do not disperse on their own, in being mode we can realize that we can choose not to react to them, because thoughts and feelings are not facts.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy relies heavily on the use of metaphors as teaching tools. One of the metaphors is A Tale of Two Wolves, which is used to illustrate the concept of thinking mode vs. sensing mode. If we picture one wolf as the “thinking wolf” and the other wolf as the “sensing wolf,” we are not trying to make the thinking wolf go away. We are simply choosing not to feed the thinking wolf by continuing to think about it. When we no longer feed the thinking wolf, it goes away on its own.

This story dramatizes the idea that thinking about not thinking is still thinking. Telling yourself, “Don’t think about it” is thinking about it by feeding the thinking wolf.

In this introduction we also reviewed some of the basic skills of mindfulness. These skills include:

- Focused Attention

- Non-judgmental Awareness

- Observing Sensations

- Cultivating Gratitude

- Compassionate Awareness

All of these mindful skills work together to increase present-moment awareness and to enhance one’s ability to “live in the now.”

Mindfulness is a type of metacognition, or “thinking about thinking.” Metacognition of this type plays a crucial role in various cognitive activities, including learning, problem-solving, decision-making, and self-regulation. For the purposes of Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, metacognition helps us to become aware of our own thoughts and feelings. This helps us to identify and modify automatic ruminating cycles that may be leading us to consequences we’d rather not experience.

One of the ways Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy develops the ability to utilize this type of metacognitive skill is through the “what” and “how” skills of mindfulness as conceptualized in Linehan’s Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). There are six of these skills. The first three teach us what to do to be mindful, and the second three teach us how to be mindful.

The “what” skills of mindful awareness are:

- Observing

- Describing

- Participating

The “how” skills of mindful awareness are:

- Being non-judgmental

- Being one-mindful

- Being effective

In this introductory chapter on mindfulness, we also reviewed some of the benefits of mindfulness, drawing on research from psychology, neuroscience, and contemplative science. It explores how mindfulness practice has been shown to reduce stress, enhance emotional regulation, improve cognitive functioning, and promote overall well-being. Some of the benefits of mindfulness include:

- Stress reduction

- Improved emotional regulation

- Enhanced cognitive functioning

- Reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression

- Better sleep quality

- Enhanced well-being and quality of life

We also briefly outlined various mindfulness techniques and practices that will be described in greater detail in later chapters, such as mindful breathing, the body scan meditation, and mindful movement.

This chapter gave a brief introduction to the skills of mindfulness, reviewing what some of the current research has to say about its benefits. The chapter also reviewed why mindfulness might be an important tool to integrate into clinical settings.