In the Greek myth of Pygmalion, an artist falls in love with a statue he has created. The great sculptor Pygmalion creates his ideal woman in marble. The statue is so beautiful that he falls in love with her. In the myth, his love for the statue is so powerful that the statue springs to life and becomes a real woman.

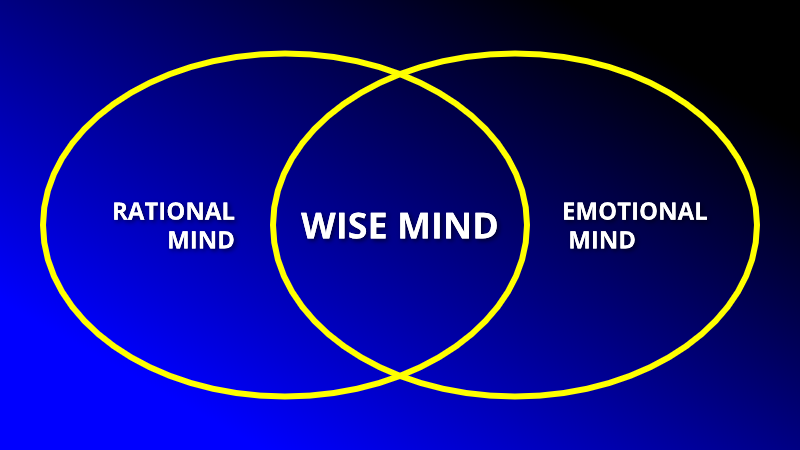

In psychology there is a concept based upon this myth. This idea is known as the Pygmalion Effect. The Pygmalion Effect states that people have a tendency to become what you believe them to be based on how you treat them. If you expect good behavior from your friends and loved ones, then that is usually what you get. On the other hand, imagine a family member who is basically a ‘good’ person who wants to please his loved ones. Yet every time this person interacts with his family members, they greet him with suspicion, always expecting the worst from him. How long do you think it would take for this person to live up to their ‘bad’ expectations?

American school teacher Jane Elliot did a famous experiment that perfectly illustrates the power of the Pygmalion Effect. During the racial tensions of the 1960s, this teacher created the Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes Experiment.

The first day of the experiment, she told her class that “blue-eyed people are superior to brown-eyed people.” She spent the day praising the blue-eyed students, while condemning the brown-eyed students. She gave the blue-eyed students privileges that the brown-eyed students didn’t get, and punished the brown-eyed students more severely than the blue-eyed students for behavioral infractions.

On the second day of the experiment, she reversed the roles, with the brown-eyed students receiving extra privileges while the blue-eyed students received more severe criticism and punishments.

As a result of the experiment, the ‘superior’ students had better behavior, better interactions, and better grades. The ‘inferior’ students had just the opposite results. In just a single day, the students had lived up (or down) to her expectations of them.

The way to harness the power of the Pygmalion Effect in your life is to always remember to be compassionate with your friends and loved ones. Let them know you love them with every word and deed.

One way to do this is to eliminate judgment from your style of interacting with others. By consciously choosing to be compassionate with them, you allow the Pygmalion Effect to work its magic. If you judge your loved ones to be unsuccessful, then your expectations will be to have an unsuccessful loved one. When you are expecting an unsuccessful partner, you tend to ignore the times when your partner does succeed, and to focus only on the times when your partner does not. By your assumptions, you have set your perception filter to only notice the times when your partner does not succeed.

If you change your assumptions to more positive outcomes, you will re-set your perception filter and thereby create a different reality in your life and in the lives of your loved ones.

People are very good at picking up on your expectations. Others tend to fulfill our expectations of them, no matter whether those expectations are positive or negative. If you have only positive expectations for your friends and family, free of judgment, your loved ones will tend to rise to the occasion and fulfill those expectations. And of course if you have only negative assumptions and expectations about your friends and family, they tend to live up to those expectations as well.

Sometimes we may think we are holding positive expectations for our loved ones, but our words and actions may convey a different message. For example, suppose you have a son named Adam. You want Adam to clean his room. This is a positive expectation because it is a positive behavior that you wish to encourage. Now take a look at the two statements below, and see which one would convey the more positive expectation, in your opinion:

Statement A:

“Adam, I can’t believe you didn’t clean your room again! This is the third time this week! I just don’t know what I’m going to do with you!”

Statement B:

“Adam, I noticed you didn’t clean your room again today. I know you didn’t mean to forget. I’m sure you’ll get around to it before the day is over. Remember, if you need help, you can always ask me.”

Which statement do you think conveys a more positive expectation? Which one would you be more likely to respond to if you were Adam?

By consciously choosing to re-frame our responses, we are able to expect the best from our loved ones and our friends. When we do so, we can harvest the power of the Pygmalion Effect.

This is a LIVE WEBINAR that will be presented on November 9, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Pacific Standard Time.

This is a LIVE WEBINAR that will be presented on November 9, 2023 at 10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Pacific Standard Time.