Successful mood management comes from successful emotional regulation. Emotional regulation means recognizing patterns of emotional aggression and stopping the cycle of emotional aggression before it starts. This means becoming aware of and attuned to your own cycles of emotions.

Before you can become attuned to your own cycles of emotional behavior, you must first be able to identify your emotions.

Society often teaches us that there are acceptable emotions to display in public, and unacceptable emotions to display in public. Those emotions that we feel safe displaying are our secondary emotions. In situations where people tend to become emotionally aggressive, there are underlying emotions driving these secondary emotions.

These underlying emotions, called primary emotions, are emotions that we do not feel safe displaying or discussing in public. If we suppress these primary emotions for long enough, it is possible that we may eventually forget what these emotions are and what they feel like. When this happens, the first step to emotional regulation is to identify these lost emotions.

By using the mindful skills of observing and describing, you can distract yourself from drowning in unpleasant emotions by simply identifying the emotions and describing their characteristics to yourself. As you step outside of the stream of feeling by distracting yourself with the process of observing and describing, it may help to name these emotions to yourself.

For example, if you’re feeling angry, repeat to yourself, “That’s anger.” As you begin to ponder this emotional state, trace it back to its origin. Are there any primary emotions driving the anger? Could it be that you are angry because you fear losing someone or something? Are you angry because of a fear of being inadequate in some area of your life? Are you angry because you are frustrated at a personal failure? The feeling behind the secondary emotion is the primary emotion.

Ruminating Cycles and Emotional Regulation

As you use your skills of observing and describing, you will not only be distracting yourself from fully experiencing the negative aspects of the mood. You will also be exploring the primary roots of the secondary emotion being experienced. As you observe and describe your emotional states to yourself, you become more emotionally aware of their origins. The more aware you are about the origins of those emotions, the more you are able to choose which emotions to give your full attention, and which emotions to let go.

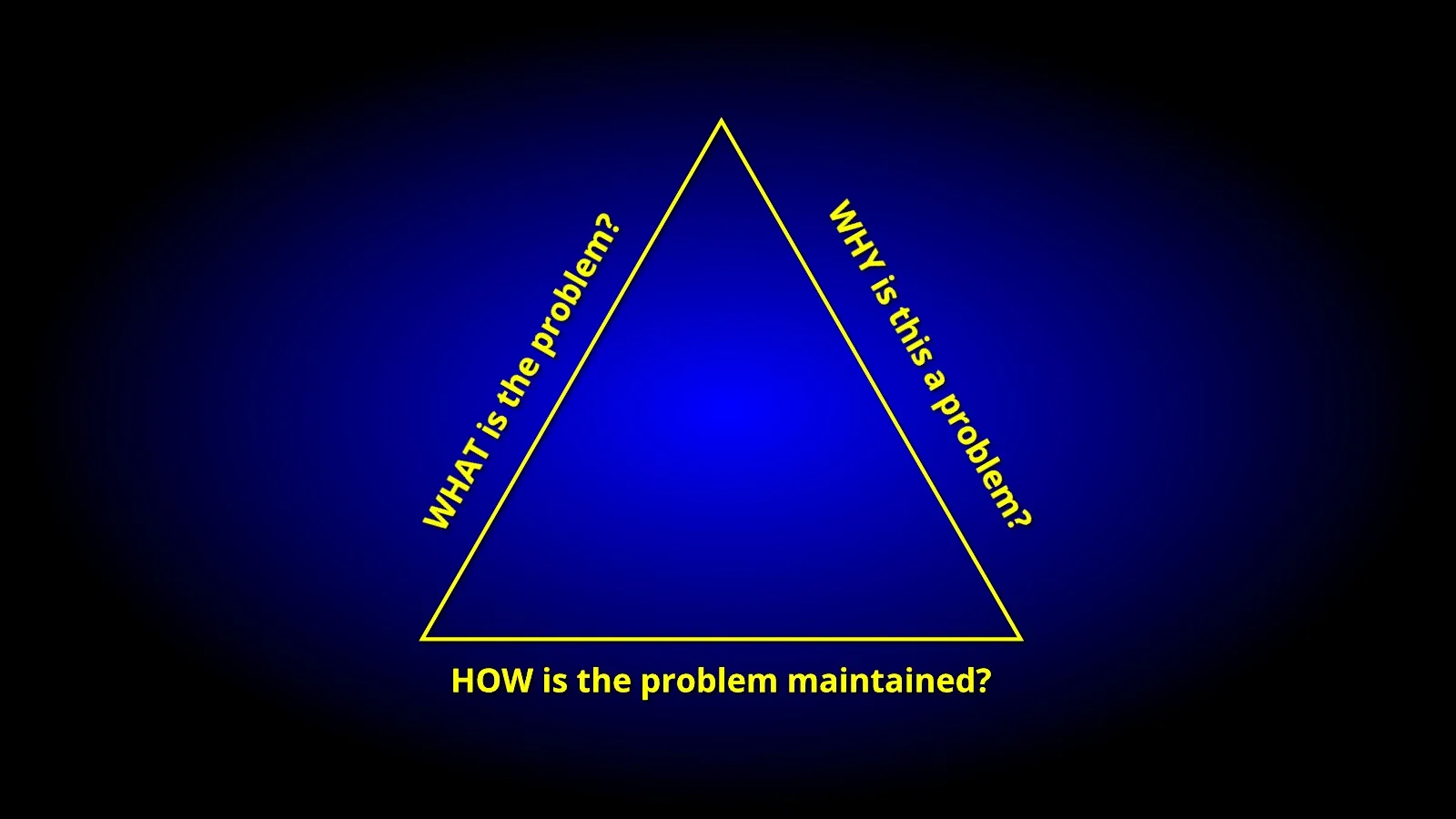

A ruminating cycle is a cycle of thought or emotion. There are positive ruminating cycles and negative ruminating cycles. Such cycles consist of the self-talk we engage in as we go about our daily business.

Let’s look at a couple of scenarios involving ruminating cycles. These cycles are from Joe and Jim. Joe’s negative ruminating cycle might look like this:

“My wife just frowned at me. I wonder what she’s upset about?”

“What have I done wrong this time?”

“Can’t I ever do anything right?”

“Why is it so hard to please her?”

“Maybe I should just divorce her and get it over with. She’s never happy.”

“I’ll show her! I’ll give her the silent treatment!”

Jim’s positive ruminating cycle might look like this:

“My wife just frowned. I wonder if she’s upset?”

“Maybe she’s just having a bad day.”

“I wonder if there’s anything I can do to help?”

“I’m happy that she trusts me enough to share her innermost feelings with me!”

Joe’s negative ruminating cycle assumes that his wife’s frown was personal in that Joe believes that his wife was frowning at him. Jim, on the other hand, simply noted that his wife had frowned, without assuming that the frown was directed at him personally. Joe also assumed that his wife’s frown was indicative of a pervasive problem: That Joe cannot ever do anything to please his wife. Jim, on the other hand, recognized that this was just one incident, and not a pervasive problem. His response to his wife’s frown was, “Maybe she’s just having a bad day.”

Finally, Joe’s ruminating cycle assumes a permanent problem: That Joe can’t “ever do anything right,” while Jim doesn’t see it as a permanent problem. He’s even willing to try to change the situation by wondering if there is anything he can do to help his wife.

Try this: The next time you find yourself in a ruminating cycle, whether it is a positive cycle or a negative cycle, begin talking out loud. Verbalize your thought and feeling patterns by observing and describing them. Look for any permanent, personal or pervasive patterns of thinking and feeling.

Be on the lookout for all-or-nothing thinking. You can usually identify such patterns of thought by looking for words like always and never. The good news about thoughts like, “Things have always been this way,” and “Things are never going to change,” is that you only need one example to disprove them. If Joe has ever done a single thing to please his wife, then he cannot say, “I can never do anything to please her.”

If Joe can find just one example of where things have gone well, then he can’t say, “I always do the wrong thing.” He might do the wrong thing 99,999 times, but if there’s even one case in which he did the right thing, then he is not justified in saying, “I always do the wrong thing.”

If Joe can think of a single time when he was able to do the right thing, then it means that it is possible to do the right thing. If it is possible to do the right thing once, it is possible to do the right thing again. All that remains is figuring out what made it possible, and repeating the conditions that made it possible.

The key point to remember about ruminating cycles is that they are self-reinforcing. Emotions like to hang around once they’ve shown up. Research has shown that once a ruminating cycle of emotional aggression gets started, we tend to act, think, and feel in ways that perpetuate the cycle. We’re conditioned to believe that when we have strong emotions, we must immediately act upon them.

Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy teaches us that we do not have to act on those emotions, and we don’t have to dwell on them. We can simply observe and describe those emotions without feeling the need to react or respond.

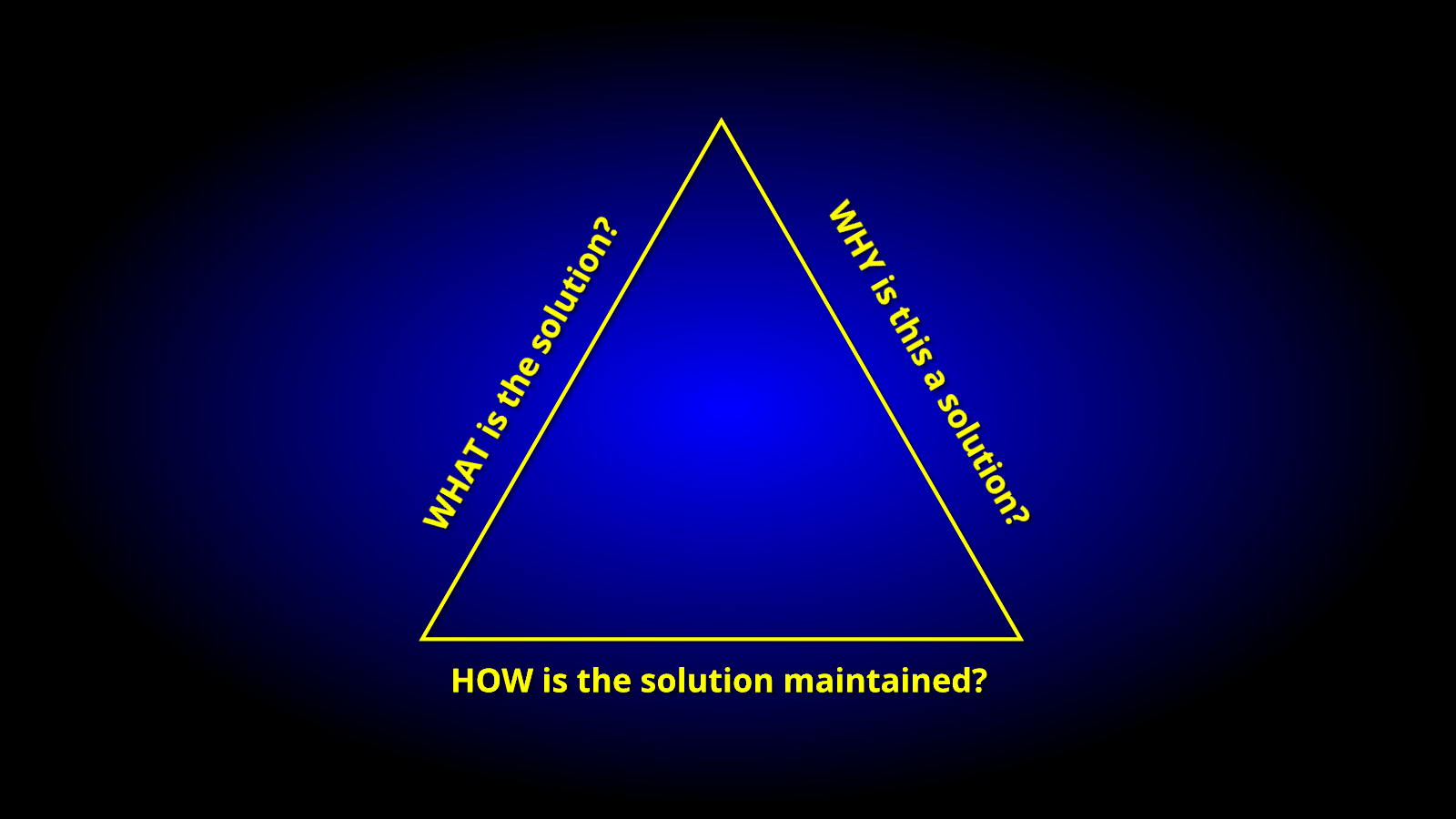

It may help to remember that there is no such thing as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ feeling. What may be considered ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is the behavior that comes after the feeling. So the problem is in the behavior, not the feeling itself. One of the behaviors that can be labeled as ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ or ‘positive’ or ‘negative,’ is the ruminating cycle itself.

It works in this way: You have a negative feeling (anger, hostility, sadness, etc.). You then activate a ruminating cycle by continuing to dwell on the feeling. As you continue to dwell on the feeling, the negative emotion feeds off of the ruminating cycle and the emotion causes you to become more and more emotionally aroused, until you act out with emotional aggression.

You can change this behavior in this way: When you note a negative emotion, simply observe it and describe it, while recognizing that you do not have to dwell on it. The feeling itself is not ‘good’ or ‘bad.’ It simply is. You can decide not to give it power over you by disengaging from the ruminating cycle. In doing so, you don’t feed the negative emotion, and it eventually subsides.

When you have mastered this, you will be well on the way to managing your moods.