The idea behind using Meme Triads is to move from a problem-focused paradigm to a solution-focused paradigm. One of the goals of using Meme Triads is to begin to think in terms of solutions instead of in terms of problems. When we start thinking in terms of solutions, we begin to live with intention. The power of intention is one of the skills of mindfulness, so by living deliberately and with intention, we move to a solution-focused paradigm.

To illustrate the difference between a problem-focused paradigm and a solution-focused paradigm, and how to move from one to another, we’ll use the example of a couple in which one or both partners are engaging in emotional aggression by expecting the other partner to be responsible for making them happy.

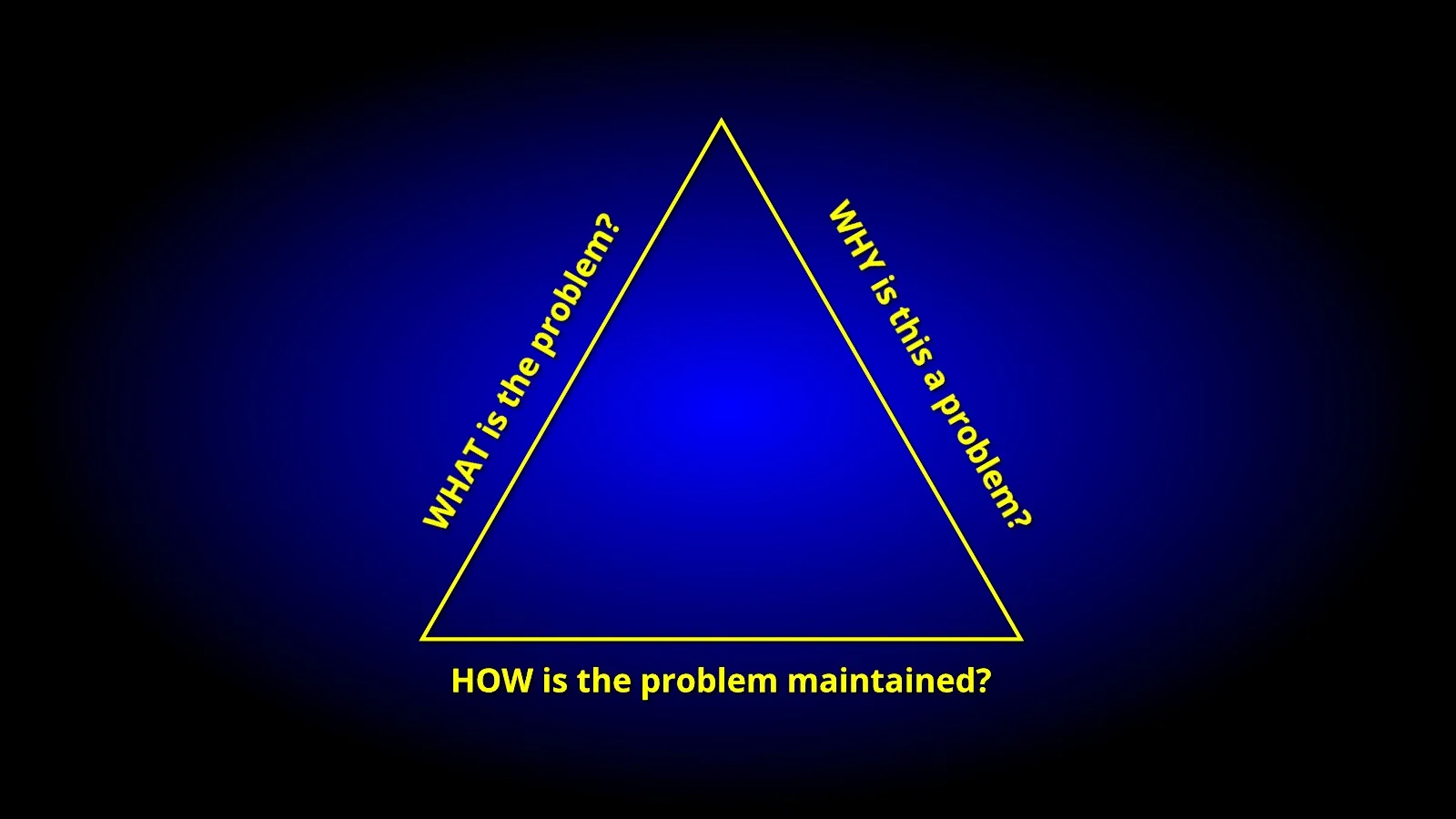

We’ll graph it out as follows:

- What is the problem? The problem meme is, “My spouse must be responsible for my happiness.”

- Why is this a problem? This is a problem because “My spouse is getting tired of being responsible for my happiness.”

- How is the problem maintained? In this example, the problem is maintained because I believe my spouse must be responsible for my happiness, but my spouse has grown tired of being responsible for my happiness. If I try to solve the problem by insisting even more that my spouse be responsible for my happiness, she reacts by getting even more tired of being responsible for it.

The first step in moving towards a solution is to eliminate the problem-based meme. Since the meme has three components, and all three components are interrelated and dependent on each other, we can choose any of the three components to change. By changing any one of the components, we transform the meme.

In the example above, we’ll look at what happens when we change any of the three components. Let’s start with the ‘What’ component. This component is, “My spouse must be responsible for my happiness.” What would happen if this component was changed to, “I will be responsible for my own happiness?”

If we make this change, what does it do to the other two components?

If the ‘What’ component is now changed to “I will be responsible for my own happiness,” let’s first look at what this does to the ‘Why’ component. The ‘Why’ component above is “My spouse is getting tired of being responsible for my happiness.” If the ‘What’ component is changed to “I will be responsible for my own happiness,” then the ‘Why’ component is altered, because if I am now responsible for my own happiness, my spouse is no longer responsible for my happiness, and has no reason to get tired.

Now let’s look at the ‘How’ component when the ‘What’ component has been changed to “I will be responsible for my own happiness.” The answer to the question, “How is the problem maintained?” is that the more tired my spouse gets of being responsible for my happiness, the more I pressure her to take on that responsibility. If the ‘What’ component has changed, and I have now learned to be responsible for my own happiness, there is no need to pressure my spouse to shoulder that responsibility.

So by changing the ‘What’ component of the triad, we have changed all three components, and transformed the meme into something more productive.

Let’s now examine what happens if we focus on changing the ‘What’ component. The ‘What’ component in the problem-focused example above is, “My spouse is getting tired of being responsible for my happiness.” In this case, I cannot change the ‘Why’ component, because it deals with my spouse’s thoughts and feelings, and not my own, and I cannot force my spouse to change her feelings if she doesn’t want to. But let’s just assume that hypothetically she decides to continue to bear the burden of my happiness, even though she is tired of it. If that is the case, what happens with the ‘How’ component?

The ‘How’ component is no longer an issue, because if my spouse has agreed to continue to bear the burden of responsibility for my happiness, even if she is tired of it, then I have no reason to continue to pressure her to do so. Therefore the ‘How’ component is no longer relevant.

So if the ‘Why’ component is altered in this way, what does it do to the ‘What’ component? If the ‘What’ component is “My spouse must be responsible for my happiness,” and my spouse has agreed to be responsible for my happiness, there is no problem (not for me, at least…my spouse may feel differently!).

Finally, let’s look at what happens when we change the ‘How’ component.

If the ‘How’ component is that I pressure my spouse to be responsible for my happiness whenever she complains that she is tired of being responsible for my happiness, I could change it by not pressuring her to take on that responsibility. If I do that, the ‘What’ component of, “My spouse must be responsible for my happiness” is irrelevant, since I am no longer pressuring her. And since I am no longer pressuring her, she no longer feels tired of the responsibility for my happiness, thereby changing the ‘Why’ component as well.

In the illustration above you can already see elements of moving from a problem-focused paradigm to a solution-focused paradigm.

Let’s take it a step further by exploring the Solution-Focused Generic Meme Triad.

Looking at the problem-focused triad above, the central issue is ‘my happiness.’ The problem manifests because I am trying to derive my happiness from the actions and feelings of someone else: My spouse.

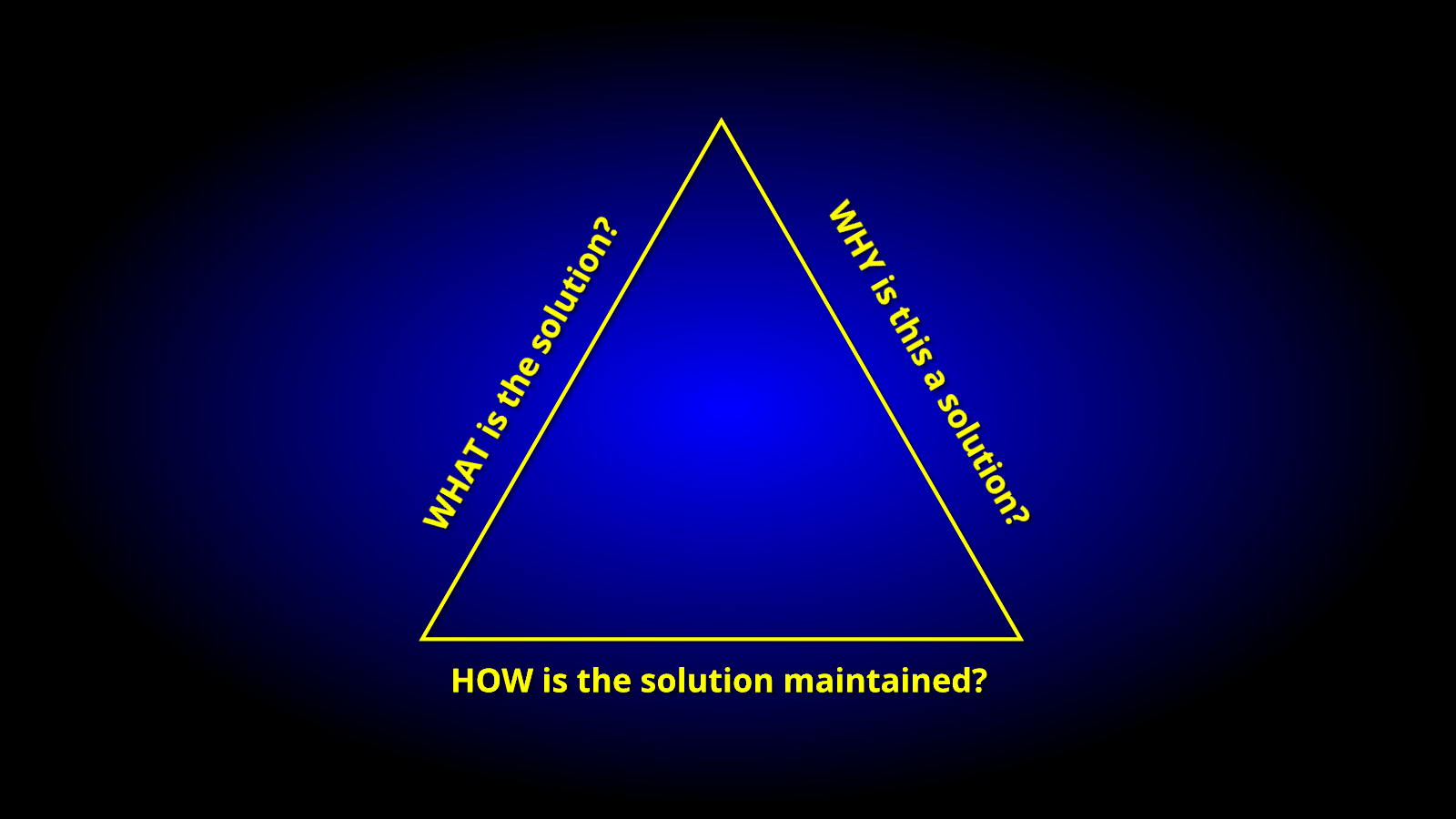

What happens when I move to a solution-focused paradigm? If the solution (or the intention) is ‘Happiness,’ the solution-focused triad becomes:

- What is the solution? I am responsible for my own happiness.

- Why is this a solution? Because if I am responsible for my own happiness, nobody else has to be responsible for my happiness. Also, if I am responsible for my own happiness, nobody else can ever take it away from me.

- How is the solution maintained? The more I am responsible for my own happiness, the less I am dependent on others for my happiness, and the less dependent on others I am for my own happiness, the happier I become.

With all of the meme triads that follow in future posts, the objective is to move from a problem-focused paradigm to a solution-focused paradigm by altering the memes that are leading to negative consequences.

By altering our memes to a solution-focused paradigm, we become proactive in creating positive consequences in our lives.