Table of Contents

High-functioning anxiety is one of the most misunderstood mental health experiences today. On the outside, people with high-functioning anxiety often appear successful, motivated, and “put together.” They meet deadlines, arrive early, achieve their goals, and consistently become the dependable ones others rely on. On the inside, however, the story is very different. There is often a constant undercurrent of worry, self-criticism, overthinking, and nervous energy that never truly shuts off.

At the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, Charlton Hall, MMFT, PhD, works with many individuals who outwardly appear to be thriving yet inwardly feel exhausted. High-functioning anxiety can quietly erode well-being, relationships, and joy, especially when it goes unrecognized or is dismissed as “just stress.” Mindfulness-based ecotherapy offers a grounded, compassionate approach to coping with high-functioning anxiety by addressing both the nervous system and the deeper patterns that keep anxiety running the show.

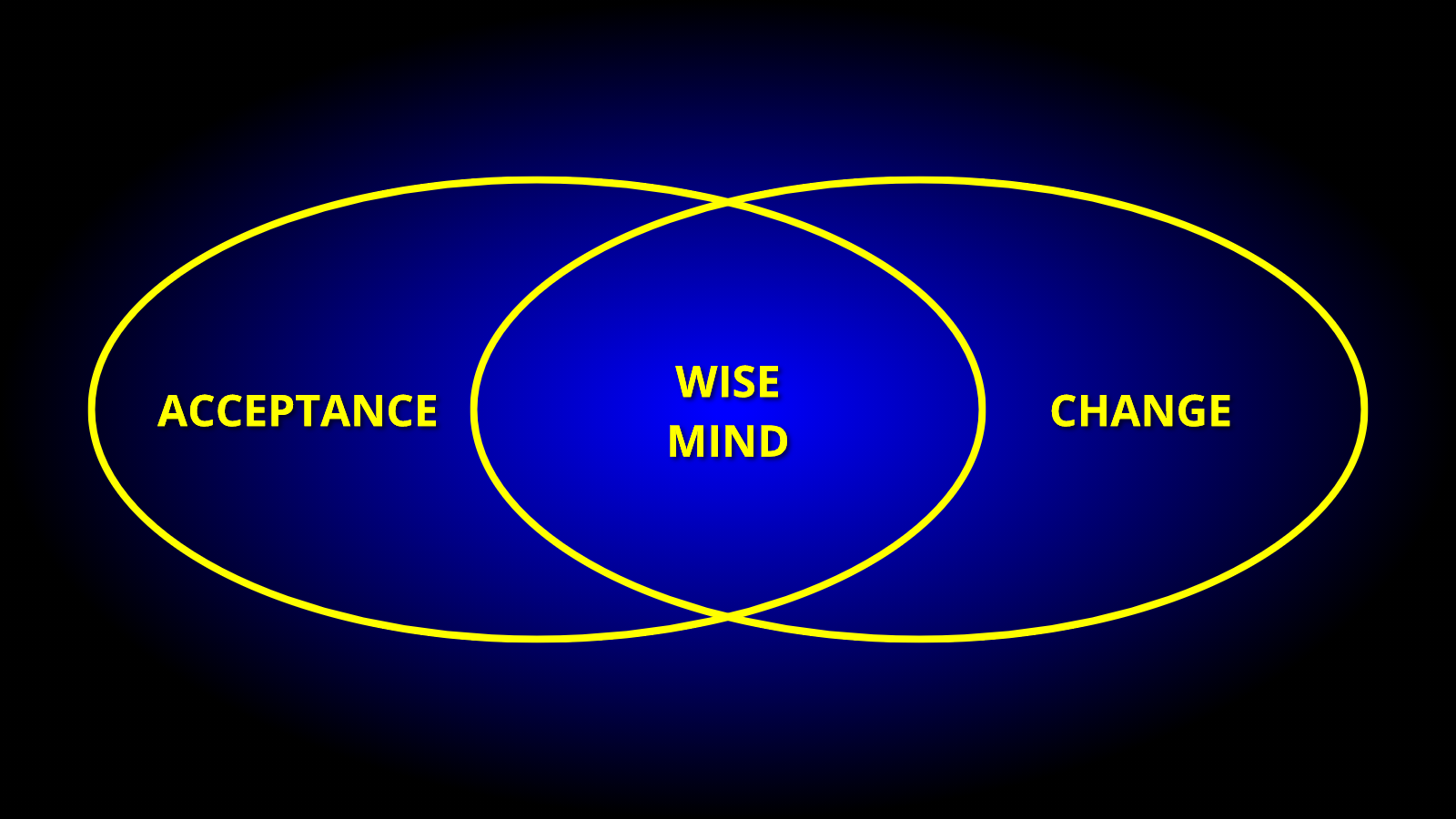

Below are seven practical, evidence-informed coping strategies for high-functioning anxiety, rooted in mindfulness-based ecotherapy and commonly integrated with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), and solution-focused approaches.

1. Name High-Functioning Anxiety Without Judgment

One of the most powerful first steps is simply recognizing high-functioning anxiety for what it is. Many people minimize their anxiety because they are still “functioning.” Mindfulness invites noticing internal experiences without labeling them as failures. Instead of “Something is wrong with me,” the practice becomes, “I’m noticing anxiety showing up right now.” This subtle shift reduces shame and creates space for intentional responses rather than automatic ones.

2. Regulate the Nervous System Through Nature-Based Grounding

Mindfulness-based ecotherapy emphasizes the calming effect of intentional connection with the natural world. Even brief, regular exposure to nature can help regulate the nervous system. Walking outdoors, noticing the sensation of wind or sunlight, or grounding attention in natural sounds can interrupt the chronic hyperarousal common in high-functioning anxiety. Nature provides a steady, nonjudgmental presence that contrasts with the constant internal pressure many anxious high-achievers experience.

3. Practice Mindful Awareness of Productivity Traps

High-functioning anxiety often disguises itself as productivity. Constant busyness can feel necessary, even virtuous, while actually reinforcing anxiety. Mindfulness helps individuals notice when productivity becomes avoidance. By gently observing urges to overwork or overprepare, clients learn to pause and ask whether an action is values-driven or anxiety-driven. This awareness is essential for creating sustainable balance.

4. Externalize the Inner Critic

A relentless inner critic is a hallmark of high-functioning anxiety. Mindfulness-based ecotherapy encourages clients to observe critical thoughts rather than fusing with them. Visualizing the inner critic as a separate voice, rather than an absolute authority, can reduce its grip. This practice aligns with ACT principles, helping people choose actions based on values rather than fear-based narratives.

5. Use Values as an Anchor, Not Anxiety

Many people with high-functioning anxiety confuse fear with motivation. While anxiety can push achievement, it rarely leads to fulfillment. Clarifying personal values provides a healthier compass. Mindfulness-based ecotherapy supports values exploration through reflective practices, journaling, and nature-based metaphors. When actions align with values rather than anxiety, individuals often report greater satisfaction and less emotional exhaustion.

6. Build Tolerance for Stillness

Stillness can feel deeply uncomfortable for those with high-functioning anxiety. Silence and rest may allow anxious thoughts to surface more clearly. Mindfulness practice gradually builds tolerance for stillness, teaching the nervous system that pausing is not dangerous. Simple practices such as mindful breathing outdoors or brief body scans can help retrain the system to associate rest with safety rather than threat.

7. Replace Control With Compassionate Flexibility

High-functioning anxiety thrives on control. Mindfulness-based ecotherapy helps people with high-functioning anxiety to loosen rigid expectations by cultivating compassionate flexibility. This does not mean lowering standards or abandoning responsibility. Instead, it involves responding to challenges with curiosity and self-compassion rather than harsh self-judgment. Over time, this approach reduces burnout and supports emotional resilience.

Moving Forward With Support

High-functioning anxiety does not need to be eliminated to live a meaningful life. The goal is not to get rid of anxiety entirely, but to change your relationship with it. Mindfulness-based ecotherapy offers practical tools for reconnecting with the body, the natural world, and personal values in ways that support long-term well-being.

At the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, Charlton Hall, MMFT, PhD, provides teletherapy that integrates mindfulness-based ecotherapy with evidence-based approaches to help you navigate high-functioning anxiety with clarity, balance, and self-compassion.

Share Your Thoughts on High-Functioning Anxiety!

What do you think? Have you experienced high-functioning anxiety? Share your thoughts in the comments below! And don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter!