Table of Contents

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) has earned a reputation as one of the most effective forms of therapy for managing intense emotions, self-destructive behaviors, and interpersonal challenges. Developed by Dr. Marsha Linehan in the late 1980s, DBT is a structured, evidence-based approach that combines cognitive-behavioral strategies with mindfulness practices. At the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, we integrate mindfulness-based ecotherapy techniques into DBT to enhance emotional regulation and promote deeper self-awareness. Here are six essential reasons why Dialectical Behavior Therapy works so effectively.

1. Mindfulness Is at the Core of Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) emphasizes mindfulness, the practice of paying deliberate attention to the present moment without judgment. By learning to observe thoughts and emotions without being overwhelmed by them, people can break cycles of reactivity that often lead to self-harm, anxiety, or relationship conflicts. In mindfulness-based ecotherapy, this practice is extended outdoors, connecting people with natural environments to enhance focus, reduce stress, and strengthen grounding. Nature becomes an ally in cultivating awareness, making DBT skills more accessible and tangible.

2. Skills Are Practical and Action-Oriented

Unlike traditional therapy that may focus primarily on insight, DBT equips you with practical skills for real-world situations. These skills are organized into four main modules: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. Patients learn to tolerate distress without resorting to harmful behaviors, manage intense emotions effectively, and communicate their needs assertively. Integrating these skills into daily life ensures that therapy is not just theoretical but transformative.

3. Validation and Acceptance Reduce Emotional Resistance

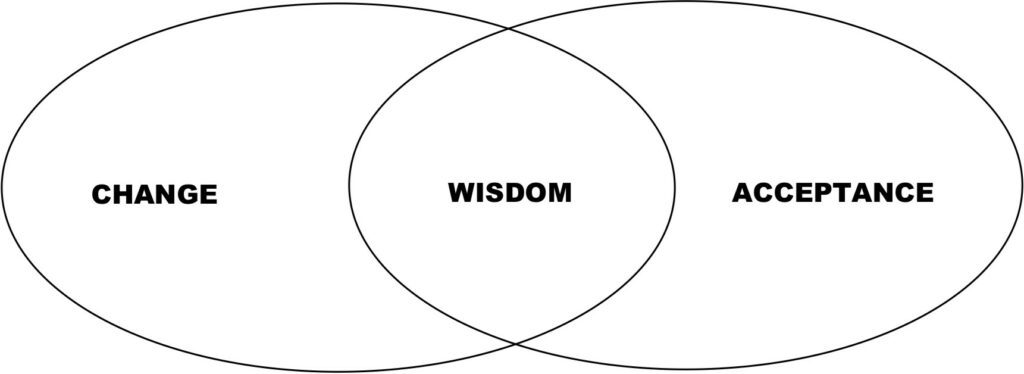

A hallmark of DBT is the balance between acceptance and change. Therapists validate clients’ experiences and emotions, acknowledging that their feelings are real and understandable. This validation reduces emotional resistance, fosters trust, and creates a safe therapeutic environment. Coupling this with nature-based experiences in ecotherapy allows clients to witness and accept the natural flow of life, enhancing the effectiveness of acceptance strategies in DBT.

4. Structured Approach Encourages Consistency

DBT follows a highly structured framework that includes individual therapy, skills training groups, phone coaching, and therapist consultation teams. This multi-layered approach provides consistent support and accountability, ensuring that clients have multiple avenues to practice and reinforce their skills. For those struggling with high-functioning anxiety or emotional dysregulation, the predictable structure of DBT can be profoundly stabilizing.

5. Focus on Building Emotional Resilience

DBT equips practitioners with tools to withstand life’s challenges. By learning to regulate emotions, tolerate distress, and navigate interpersonal dynamics, clients develop resilience that supports long-term well-being. Integrating ecotherapy amplifies this effect, as time in nature naturally reduces stress hormones, improves mood, and strengthens adaptive coping mechanisms. The combination of DBT and mindfulness-based ecotherapy creates a holistic pathway to emotional resilience.

6. Evidence-Based Success Across Diverse Populations

Research has repeatedly shown DBT’s effectiveness for people with borderline personality disorder, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and self-harming behaviors. Its adaptability makes it effective for a wide range of clients, including those who may not respond to traditional talk therapy. When combined with ecotherapy principles, DBT can be tailored to each person’s needs, providing individualized support that addresses both psychological and environmental factors.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy works because it blends mindfulness, practical skills, validation, structured support, emotional resilience, and evidence-based practices into a cohesive therapeutic model. At the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, we enhance DBT by integrating ecotherapy experiences, helping clients connect with both themselves and the natural world. This integration deepens mindfulness, strengthens coping skills, and supports long-term emotional well-being.

DBT is a roadmap for living with awareness, acceptance, and adaptability. By combining its proven techniques with the grounding benefits of nature, you too can find relief from emotional turbulence and discover a sense of calm, connection, and clarity.

Share Your Thoughts on Dialectical Behavior Therapy!

What do you think? Share your thoughts in the comments below! And don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter!