At this time of year we like to dress up and often wear masks. But there are other kinds of mask that we sometimes wear to hide our emotions. One of these emotional masks is the mask of anger.

Anger is almost always a mask for deeper emotions. When we are angry, that anger is usually the result of failed attempts to express more positive emotions. These more positive emotions are two-sided. When we cannot express our love and concern for others in positive ways, anger is the result.

You may have heard that hate is the opposite of love. Anger and other forms of emotional aggression may sometimes be interpreted as hatred. But consider this: Have you ever been angry with someone or something you didn’t care about? If you didn’t care one way or another about how things turned out, would there be any reason to get angry about it?

The opposite of ‘love’ isn’t ‘hate.’ The opposite of ‘love’ isn’t ‘anger.’ The opposite of ‘love’ is ‘indifference.’ The opposite of ‘love’ is ‘apathy.’

This doesn’t mean that we can justify emotionally aggressive tendencies by saying that they are just expressions of how much we care. We don’t get to say, “I yell at you because I care about you.” If we truly care about others, we will reflect that intention in positive ways. If we really care about the people in our lives, we will express that care by learning to interact without emotional aggression.

Anger and other forms of emotional aggression are often hiding deeper emotions. These emotions, called primary emotions, are feelings that deal with our own vulnerability. If I am feeling insecure about a relationship, or about my own ability to cope, or if I am feeling abandoned or betrayed, I am in a vulnerable state.

Vulnerability is difficult to express openly because we are conditioned to believe that if we express such feelings then it is easier for others to take advantage of us. So when we are feeling vulnerable because of our own insecurities or fears, the tendency is to mask those feelings of vulnerability by acting out in emotionally aggressive ways. We’re taught to “suck it up,” or that “big boys don’t cry,” or that “you shouldn’t let him get to you.” So it’s natural to want to hide these emotions by masking them with anger.

Anger and emotional aggression are attempts to do something to fix the problem. Anger is Doing Mode. The first step in using mindfulness to manage our moods is to realize that we don’t have to ‘do’ anything in response to an emotional state. By shifting to Being Mode, it is possible to simply sit with the vulnerable emotions that led to the emotional aggression in the first place.

Always remember that there is no such thing as a ‘wrong’ feeling. Problems arise from how we choose to behave after the feeling. By consciously choosing to sit with those feelings of vulnerability and insecurity in Being Mode instead of believing that we have to act on them by ‘doing’ something to fix the problem, we use mindfulness to realize that feelings are simply feelings, and that they will eventually pass.

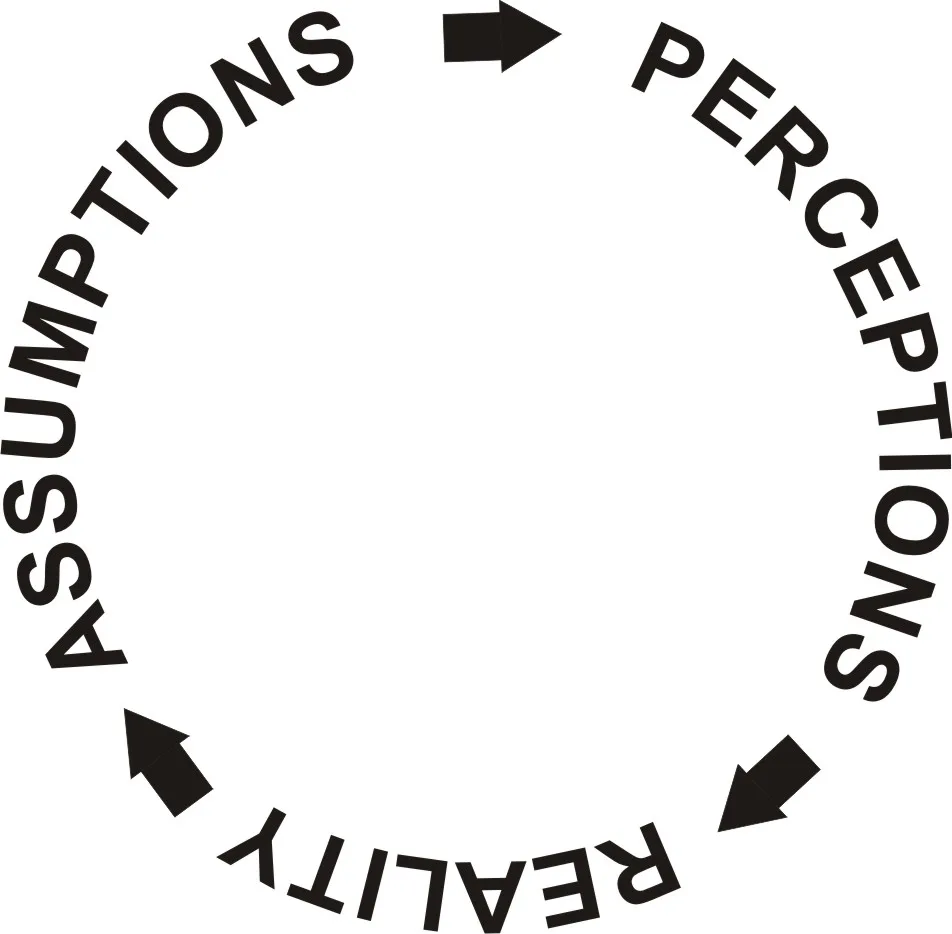

The most primitive parts of the brain are sometimes colloquially referred to as the reptilian brain. These are the parts of the brain that are only concerned with the four basic necessities of survival: Food, fighting, fleeing, and reproduction. Anger often leads to aggression because of the ‘fight or flight’ response of the reptilian brain. This part of the brain senses danger before the rational parts of the brain can kick in.

Imagine that one morning on the way to work you catch a glimpse of the garden hose out of the corner of your eye. Further suppose that in your haste to go about your morning routine, your brain doesn’t recognize it as the garden hose, but instead interprets it as a snake. The first thing that happens is that you have an automatic visceral reaction. Your ‘fight or flight’ response kicks in. You have a physiological response. You may gasp out loud, or freeze in place. This is the reptilian brain taking charge.

The next thing that happens is that your emotional brain kicks in. When this part of your brain is activated, you have an emotional response. In this case, you may experience a brief flash of fear.

Finally, the rational, thinking part of your brain is activated. You think, “Oh, that’s just the garden hose.”

Your rational response then defuses the ‘fight or flight’ response and you realize that there is no actual danger there.

What if that thinking part of your brain didn’t recognize it as a garden hose? Would you grab a hoe and bludgeon your garden hose to death? Would you rush to the car hoping to avoid the danger? Would you freeze in place?

Emotional aggression is the tendency to respond from the reptilian brain before the rational parts of the brain have had a chance to do their job.

Emotions like anger are usually visceral, reptilian brain responses, but with practice it is possible to learn that we don’t have to respond every time we feel an overpowering emotion. Learning to sit mindfully with an emotion, without responding or reacting to it, is living in the moment.

By learning to ‘wait out’ extreme emotional responses, we give our rational brains time to catch up and to then come up with positive solutions that don’t require aggressive responses.