Table of Contents

Radical acceptance is one of the most powerful and misunderstood skills in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy. You are often taught, implicitly or explicitly, that uncomfortable emotions must be fixed, suppressed, or eliminated. Radical acceptance offers a different and far more effective approach. It teaches you that you can experience emotions and thoughts fully without engaging in behavioral cycles that lead to negative consequences. You learn that pain is part of being human, but suffering is often optional.

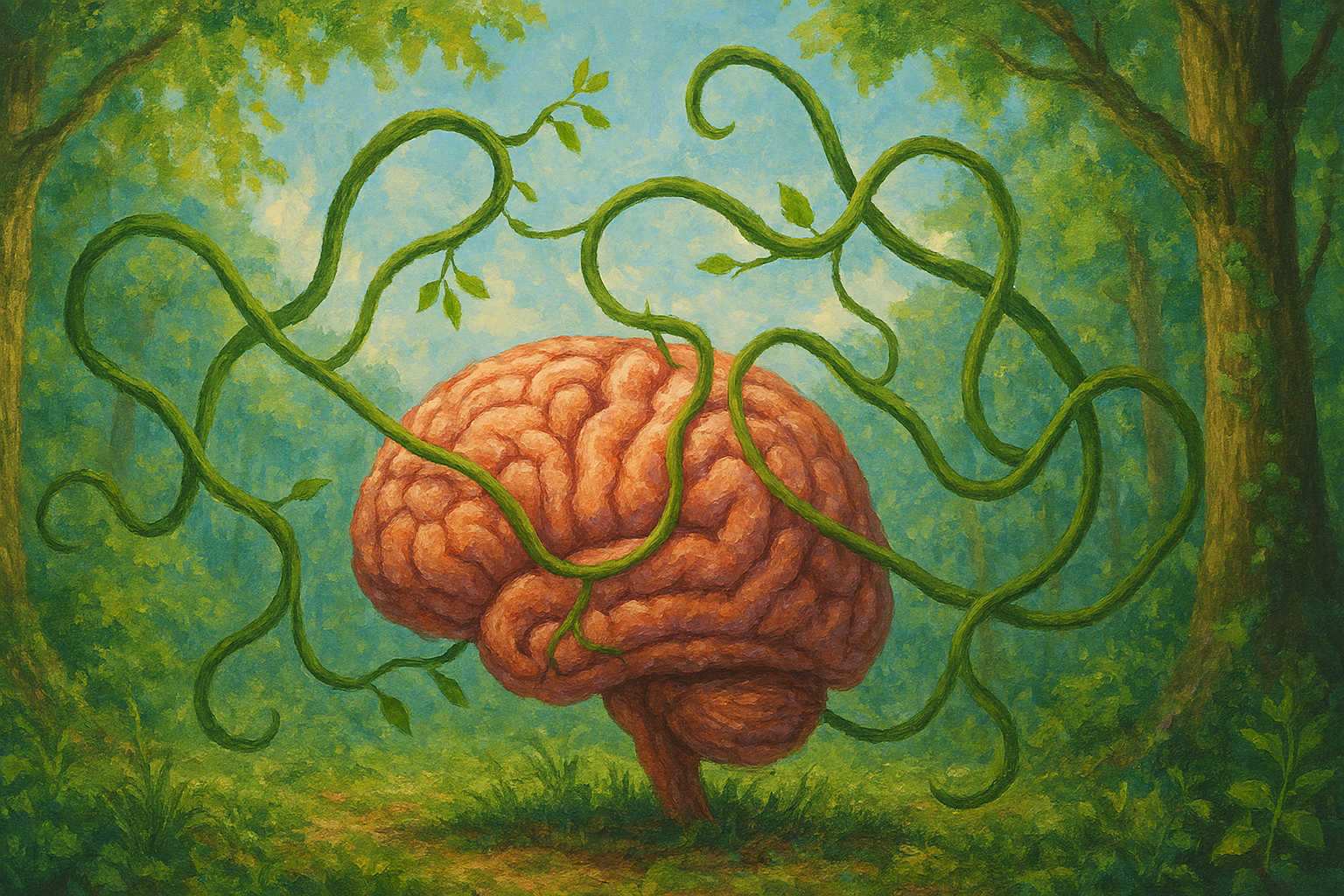

The Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy skill of radical acceptance teaches you that you are not your thoughts and you are not your emotions. Thoughts and feelings are not commands, identities, or truths. They are temporary processes of the brain, shaped by learning, memory, trauma, biology, and context. When you fuse with them, believing they define who you are or dictate what you must do, you lose flexibility. When you relate to them with awareness and acceptance, you regain choice.

Radical Acceptance and the Shift From Reaction to Response

Radical acceptance does not mean liking what is happening, approving of harm, or giving up on change. It means clearly acknowledging reality as it is in this moment, without adding layers of resistance. When you fight reality internally, your nervous system remains activated, keeping you locked in cycles of anxiety, anger, shame, or avoidance. Research consistently shows that experiential avoidance, the attempt to escape unwanted internal experiences, is strongly linked to psychological distress and maladaptive behavior (Hayes et al., 2020).

When you practice radical acceptance, you stop arguing with what already exists. You allow thoughts to arise and pass. You allow emotions to move through the body. This creates space between what you feel and what you do. Instead of reacting automatically, you respond intentionally. This skill is foundational in mindfulness-based and acceptance-based therapies, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Dialectical Behavior Therapy, both of which emphasize acceptance as a pathway to psychological flexibility (Linehan, 2020; Hayes et al., 2020).

You Are Not Your Thoughts or Emotions

One of the most liberating aspects of radical acceptance is learning to defuse from internal experiences. A thought like “I am failing” is no longer treated as a fact. An emotion like fear is no longer treated as a threat that must be eliminated. Instead, thoughts are seen as mental events and emotions as physiological and psychological processes. Neuroscience research supports this perspective, showing that emotional experiences are dynamic brain-body states that change when they are observed with nonjudgmental awareness rather than suppressed or amplified (Dahl et al., 2020).

This shift matters because behavior follows relationship, not content. When you believe your thoughts unquestioningly, you act as if they are instructions. When you accept their presence without attachment, you gain the freedom to choose actions aligned with your values rather than your impulses.

Radical Acceptance in Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy

In Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy, radical acceptance is practiced not only internally but also in relationship with the natural world. Nature offers constant demonstrations of acceptance without resignation. A river does not resist obstacles; it moves around them. A forest does not judge decay; it integrates it into renewal. When you practice radical acceptance outdoors, your body often understands the lesson before your mind catches up.

Ecotherapy supports radical acceptance by engaging your senses and grounding you in the present moment. Sitting with discomfort while noticing birdsong or the rhythm of waves can regulate the nervous system, making acceptance more accessible. Research since 2020 shows that nature-based mindfulness practices reduce rumination and emotional reactivity while increasing psychological flexibility and self-regulation (Schutte & Malouff, 2021; Passmore & Howell, 2020).

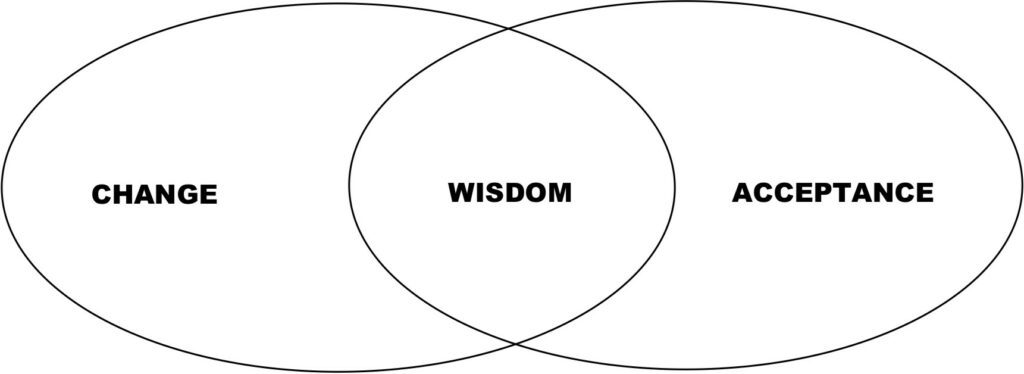

Acceptance Is the Doorway to Change

Paradoxically, radical acceptance is what allows meaningful change to occur. When you stop wasting energy fighting internal experiences, that energy becomes available for skillful action. You can feel anger without acting aggressively. You can feel anxiety without avoiding life. You can feel sadness without collapsing into hopelessness. Acceptance creates stability. Stability creates choice.

At the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, radical acceptance is taught as a lived practice,. You learn to notice when resistance shows up in your body, your thoughts, and your behaviors. You learn to soften your grip. Over time, you experience a quiet but profound shift. Life becomes less about controlling what you feel and more about living fully, even when feelings are difficult.

To explore how radical acceptance and other Mindfulness-Based Ecotherapy skills can support your well-being, visit www.mindfulecotherapycenter.com

References

Dahl, C. J., Wilson-Mendenhall, C. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2020). The plasticity of well-being: A training-based framework for the cultivation of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(51), 32197–32206. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014859117

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2020). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Linehan, M. M. (2020). DBT skills training manual (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Passmore, H. A., & Howell, A. J. (2020). Nature involvement increases hedonic and eudaimonic well-being: A two-week experimental study. Ecopsychology, 12(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2019.0025

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2021). Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: A meta-analytic investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 179, 110984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110984

Share Your Thoughts About Radical Acceptance!

What do you think? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

And don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter!